Family, friends, colleagues, students and postdocs, alumni, distinguished guests.

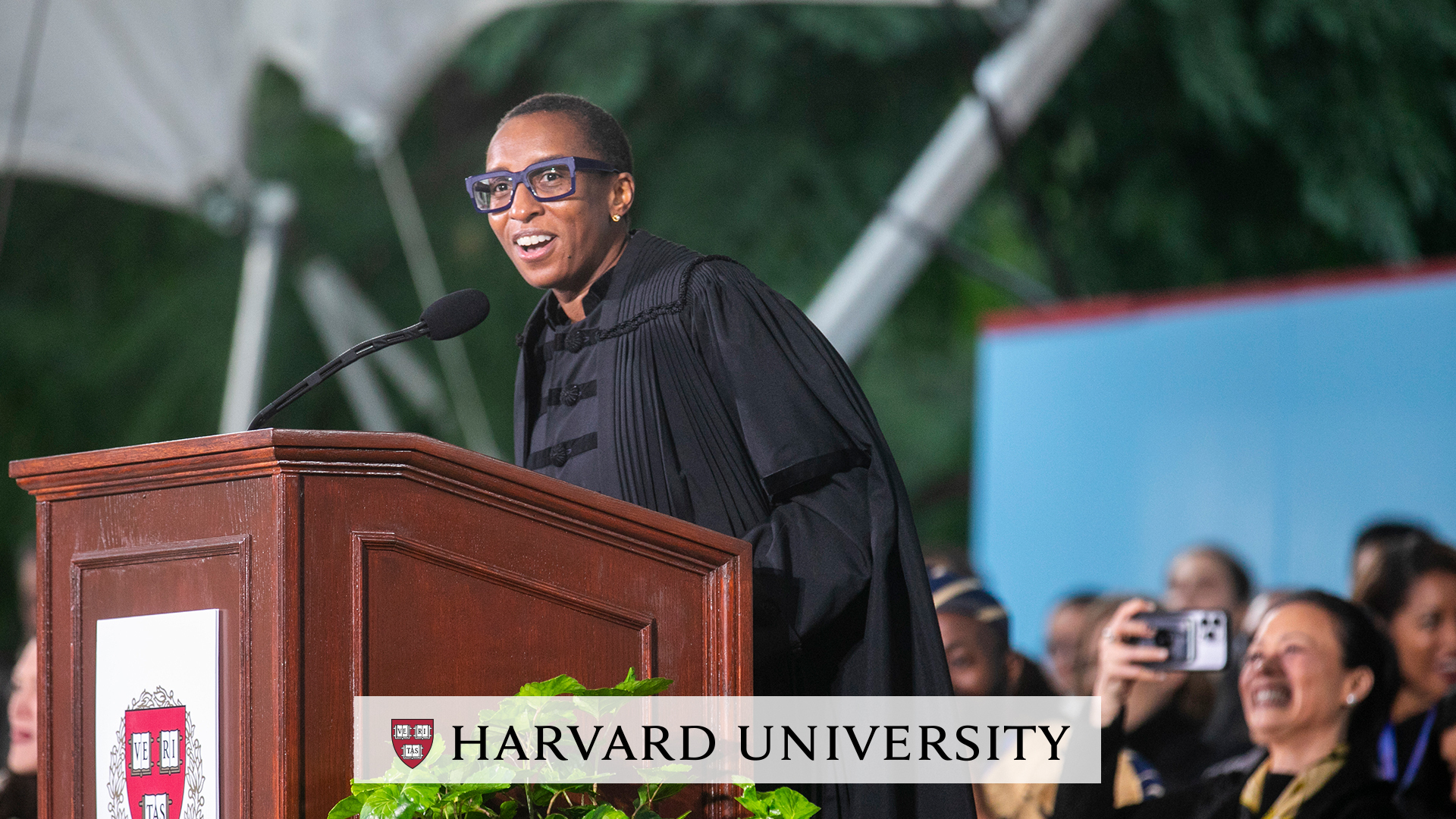

I stand before you today humbled by the prospect of leading Harvard, emboldened by the trust you have placed in me, and energized by your own commitment to this singular institution and to the common cause of higher education.

I am grateful beyond measure to the Governing Boards for placing their confidence in me; to my predecessors for offering their perspectives, their wisdom, and their support; to my colleagues and mentors, from this University and beyond, for leading in ways that continue to guide and inspire me.

I am thankful to the many members of our campus community who have worked so hard, for so many months, to make today’s event possible.

And, most of all, I am uplifted by love, love that has empowered and sustained me for as long as I can remember, love that has made me who I am.

My dad, Sony Gay, is unmatched in his optimism and in his curiosity about people and the world, twin gifts that he passed on to my brother and me.

My mom, Claudette Gay, passed away earlier this year but not before learning of my election and smiling broadly at the news. I wish very much that she were here, if only for the chance to hear her say, “I told you so.”

Both of my parents, each on their own, left everything they knew in Haiti to forge new lives in the United States. And because they understood that coming to America was not enough, they eagerly sought college education—to ensure the future they wanted for themselves and for their family.

That future came to include my best friend and my wonderful husband, Chris Afendulis. Marrying Chris remains the best decision I ever made. He has always put our family first. He makes this day—and every day to come—possible for me.

And our beloved son, Costa. In moments big and small, and with the many gifts he has already begun to share with the world, he reminds me of the meaning of the work before me, the work before all of us, and our responsibility to the future.

For nearly twenty generations, Harvard presidents have upheld that precious trust. I feel the presence of those twenty-nine predecessors here today. And the three former presidents sharing the stage with me, no strangers to this podium, have set a high rhetorical bar. Though Drew Faust helpfully pointed out in her address that “inaugural speeches are a peculiar genre…by definition pronouncements by individuals who don’t yet know what they are talking about.”

I claim no exception for my remarks today. But I will attempt to defy the genre by talking about one thing I do know—and that is the importance of courage, without which my presence here today would not be possible.

Not four hundred yards from where I stand, some four centuries ago, four enslaved people—Titus, Venus, Bilhah, and Juba—lived and worked in Wadsworth House as the personal property of the president of Harvard University. My story is not their story. I am a daughter of Haitian immigrants to this country. But our stories—and the stories of the many trailblazers between us—are linked by this institution’s long history of exclusion and the long journey of resistance and resilience to overcome it.

And because of the collective courage of all those who walked that impossible distance, across centuries, and dared to create a different future, I stand before you on this stage—in this distinguished company and magnificent theatre, at this moment of challenge in our nation and in the world, with the weight and honor of being a “first”—able to say, “I am Claudine Gay, the president of Harvard University.”

Their courage, that courage, is what I want to reflect on today: The courage of this University—our resolve, against all odds—to question the world as it is and imagine and make a better one. It is what Harvard was made to do. John Adams drafted it right into the Massachusetts Constitution, to ratify our charter, celebrating the “university at Cambridge” where “wisdom and knowledge…diffused generally among the body of the people” could “preserv[e]…their rights and liberties,” spread “the opportunities and advantages of education,” and “inculcate the principles of humanity.” By continually recommitting ourselves to our central purpose, with renewed vision and vigor, we advance the prospects of humankind.

And, as every generation must believe of its own time, never have those tasks felt more urgent.

What we offer to the world will depend on Harvard’s courage—our courage—to ask two questions that propel our work—Why? and Why not? And it will depend on the courage to answer, with confidence, two others: Why here? and Why now?

Why? is a question that comes to us early in life. If you know a young child, you know this well: Why are we here? Why is the moon out during the day? Why can’t I eat ice cream for breakfast? Why is she talking so much? We may be tempted to stop asking why when we accept the default answers around us, until something sparks us to question those answers.

Harvard has always been a place to ask Why? It animates our research and teaching.

Why? is the question of scientific breakthroughs, archival discoveries, fresh artistic forms, new remedies for physical and social ills.

Why? rights wrongs, overturns conventional wisdom, and opens the blue sky of human pursuit and possibility.

Why? is how students and faculty move toward discovery and challenge each other to push to the next levels of understanding and insight.

This simple query is the very basis of academic life.

Ideally, we shouldn’t need courage to ask Why? We should feel no more danger of recrimination or risk of censure than a young child. But Why? pokes at things. It raises doubts and raises eyebrows. It clashes with those who may prefer, as President Kennedy once said, “the comfort of opinion without the discomfort of thought.” To persist with Why? is to give up the safety of silence, the ease of idle chatter, the satisfaction of an echo chamber. The goal of Why? is not comfort, it is knowledge. Knowledge is what transforms lives. Knowledge is our purpose.

We serve that purpose best when we commit to open inquiry and freedom of expression as foundational values of our academic community. Our individual and collective capacity for discovery depends on our willingness to debate ideas; to expose and reconsider assumptions; to marshal facts and evidence; to talk and to listen with care and humility, and with the goal of deeper understanding and as seekers of truth.

The political philosopher John Rawls—who spent 30 years on the Harvard faculty—would teach his magisterial work, A Theory of Justice, alongside the works of those who most powerfully disagreed with him, encouraging his students to “listen for the music”—harmony, counterpoint, and all.

In that same spirit, when we embrace diversity—of backgrounds, lived experiences, and perspectives—as an institutional imperative, it’s not with a secret hope for calm or consensus. It’s because we believe in the value of dynamic engagement and the learning that happens when ideas and opinions collide. Communities that welcome diverse perspectives thrive not because they endorse all as valid but because they question all on their merits.

Now, all of this is easy to salute in the abstract, especially from these rarefied heights. But it is hard to protect in practice. Debate and the inclusion of diverse viewpoints and experiences, while essential for our work, are not always easy to live with. They can be a recipe for discomfort, fired in the heat of social media and partisan rancor. And discomfort can weaken our resolve and make us vulnerable to a rhetoric of control and containment that has no place in the academy. That is when we must summon the courage to be Harvard. To love truth enough to endure the challenge of truth-seeking and truth-telling. To love truth enough to ask Why?

The desire to understand the world urges us to ask Why? The hope to improve the world compels us to ask Why not?

Why not? is a call to action, the aspiration to do what might seem impossible:

Why not improve health care in Haiti and Rwanda?

Why not get the innocent off death row?

Why not map the 100 billion neurons of the brain or close persistent gaps in education from pre-K to adult learners?

Why not fight the climate crisis on every front or keep lit the flame of exploration—in the darkest depths of the sea and the furthest reaches of space-time?

Asking Why not? should be a Harvard refrain—the willingness to sound foolish, risk ridicule, be dismissed as a dreamer. We’ve seen it time and again—the courage to take a chance, even when success seems beyond reach. And the courage to collaborate, to listen, to compromise, to grow. To bring our imaginations and talents together in a different way.

I witnessed the power of asking Why not? as dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences when this space was largely emptied by a pandemic and quieted by uncertainty. We might have faltered. Many did. But we dared to work together—faculty, staff, students. Schools across the University shared ideas, resources—and our strength. We set aside long-held assumptions about teaching and research, we rethought the nature of our community, we broke down barriers to collaboration. We acted quickly and decisively, with a strong sense of shared purpose, and became a model for others. I had never been prouder to be part of this University.

When I envision Harvard on our 400th anniversary, just 13 years away, I see an institution that connects in new and expanded ways, among ourselves and with society—an institution whose people ask Why not? as eagerly as they ask Why?

Why not improve people’s lives everywhere through our scholarship, outreach, and partnerships?

By building new coalitions with citizens, industry, and government, we can accelerate the discovery and dissemination of new knowledge and effective ideas to serve the public good. On every matter of consequence, from disorders of the mind and body to disorders of the body politic, we have work to do.

Why not reach as many people as possible through our educational programs?

By using new forms of how and where we teach, hard-won during the pandemic and boosted by new technologies, we can reach more learners, change more lives, and bring the power of education to communities far beyond our campuses.

Why not open our treasure troves of books, objects, and artifacts to the world?

By increasing access to our magnificent collections, verging now on half a billion items, we cast the myriad elements of civilization into the living world—in all their error, and wisdom, and beauty—to be reconsidered, remade, and remembered by the next generation.

When we summon our courage to ask Why not?, to join new ways of thinking with new ways of acting, we expand the possibilities of what Harvard can be and what Harvard can do for the world.

We also foster the courage of those who dare to ask Why not me? A simple question that can spark profound change. The moment Margaret Fuller talked her way into the Harvard library, when women were excluded from the entire institution, and went on to publish foundational works on feminism and human rights. The day Ralph Bunche sought a graduate fellowship to Harvard’s government department and went on to help dismantle colonialism and arrange a cease-fire in the Middle East that would win him the Nobel Peace Prize.

There are many among us here today whose presence would be unimaginable were it not for their courage to ask Why not me?

Which leads us, finally, to Why here? and Why now?

Harvard is blessed with outsized capacity to seek truth and to do good, imbued with awesome potential to change the lives of individuals and the prospects of communities. This means that asking Why? and Why not? is not enough—can never be enough. Harvard has a special responsibility.

A responsibility to help anchor our democracy—by cultivating norms and values essential to a free society and by ensuring the free flow of knowledge not only among students and faculty but to all citizens to enable them to make informed decisions.

A responsibility to explore, define, and help solve the most vexing problems of society—the struggle against tyranny, poverty, disease, and war; the challenge of protecting a planet and its people from the devastation of climate change.

A responsibility to create opportunity—by identifying talent and promise wherever it resides and bringing that talent to Harvard. We are still on a journey that began in earnest with President Conant—to draw from a deeper pool of talent and provide our institution with the excellence it deserves and our diverse society with the leaders it needs and expects.

Of course, we cannot do these things alone. Joining us today are delegates from institutions representing states and nations near and far, and our trusted partners from state and local government who make possible our collective contributions to the country and to the Commonwealth. I hope that today strengthens our connections. You give us courage. The most compelling answer to Why here? can be found in the way we work together to help others thrive.

How well we are doing depends on who you ask. According to some recent surveys, almost 40 percent of Americans believe higher education has a negative effect on the country, a majority think that earning a four-year degree is a bad bet, and still others that a college education doesn’t matter at all. And these views persist despite volumes of evidence demonstrating the critical role of education for economic mobility and for individual and family well-being.

And in that paradox lies the answer to Why now?

Because “now” needs us so that “later” has a fighting chance.

We are in a moment of declining trust in institutions of all kinds. Of endless access to information, but doubts and conflict about whom and what to believe. Of political polarization so extreme that gridlock is preferred to pragmatic collaboration. And all the while, the planet warms, inequality grows, democracies falter, and the next pandemic looms.

If not now, then when?

Rebuilding trust in the mission and institutions of higher education won’t be easy. It lies partly in our courage to face our imperfections and mistakes, and to turn outward with a fresh and open spirit—meeting a doubtful and restless society with audacious and uplifting ambitions, present in both the research we undertake and the students we educate, present in the world we are changing every day by fulfilling our mission.

Courage is hard, and hard to sustain. But we see it everywhere, steady in the face of war and injustice, sickness and loss, in stories of perseverance for a greater purpose. Fourteen years after he graduated from Harvard, W.E.B. Du Bois founded the NAACP and a newspaper called “The Crisis,” an extraordinary record of the struggle for human rights, where he published the poems of a young man working odd jobs named Langston Hughes. In one of Hughes’s poems, a mother says to her son, “Life for me ain’t been no crystal stair.” Still, she tells him, she’s “been a-climbin’ on”—through “the tacks … and splinters, / and boards torn up.” And so, she implores him, “don’t you turn back. / Don’t you set down on the steps.” She gives him an example—not of reaching a goal but of pushing through difficulty, no matter the impediments, because pushing through is the only way of moving forward.

Courage is a disposition. It does not whine, or complain, or wring its hands. It also does not pretend that risk and challenge do not exist. Courage faces fear and finds resolve. And so must we hold fast to our purpose in a dangerous and skeptical world. Far from defending an ivory tower, we strive for a staircase open to all. An upward path with no boards torn up. Not only for our students but for the billions of people who will never set foot in Harvard Yard, yet whose lives may advance a step because of what we do.

It is as true today as it was when my parents mustered the courage to leave Port-au-Prince: If you want to build a better life, if you want to build a better world, higher education is the best foundation. Not because we are perfect. We are not. But because we find the courage to admit our imperfections. Because imperfection leaves room for improvement, room to ascend beyond anything we can dream of today.

I began this address claiming that I know something about courage. A bold claim, perhaps. But not a boastful one. Courage abides in a kind of purposeful detachment, admitting our fears and false steps even as we advance—to paraphrase Sojourner Truth, not allowing our light to be determined by the darkness around us. And in courage, we find freedom—where we dare to imagine and make a different future together.

I learned it from my parents who built a life of quiet achievement and high expectations that opened a world of possibility for my brother and me. I witnessed it on this campus, when the entire community reorganized itself during COVID, a feat of collective epigenetics that refashioned our institutional DNA. You have seen it, too, over four centuries—in the short walk, and long journey, from Wadsworth House to this podium today. That is the courage to be Harvard.

I have loved this place since the day I arrived as a graduate student in 1992. Now you have given me the great honor of leading this University into the future, setting a compass by its constellation of brilliant—if sometimes unruly—stars.

Let us summon the courage to be the Harvard that the world needs now.

The courage to preserve the openness and diversity we need to ask Why? and the visionary courage to ask Why not?

The courage to “listen for the music” in other points of view.

The courage to admit our mistakes and confront our shortcomings.

The courage to convert disruption into forces of renewal and reinvention.

Why not here? Why not now? We have it in each of us. We can see it in one another.

Let us be courageous together. Thank you