Native American Heritage Month

Harvard, like so many American institutions, is addressing its uneven history with Native American people while also nuturing the next generations of Native students.

Wrapped in tradition

The blanket seen behind this text was part of Harvard University's Native American Program’s blanket ceremony, held during commencement to celebrate graduating students.

Learn more about the ceremonyHarvard University is located on the traditional and ancestral land of the Massachusett, the original inhabitants of what is now known as Boston and Cambridge. We pay respect to the people of the Massachusett Tribe, past and present, and honor the land itself which remains sacred to the Massachusett People. Learn more from the Harvard University Native American Program

Leading today

Kelli Mosteller

The new executive director of the Harvard University Native American Program says her goals include highlighting the initiative’s importance to Indigenous communities and strengthening the University’s bonds with them.

Shawon Kinew

The assistant professor’s course “The First Americans: Portraits of Indigenous Diplomacy and Power” gives students a chance to have a conversation with a part of U.S. history that is often overlooked.

Philip Deloria

“Harvard is an elite institution well aware of its obligations to lead critical conversations about justice and equity, politics and policy, the past, present, and the future,” says the professor of Native American indigenous studies.

Empowering tomorrow

Victor Lopez-Carmen

“I’m humbled and relieved that this powerful medical organization saw the merits in the work that needs to be done around promoting Indigenous health, Indigenous rights, and inclusion in medical education,” says the HMS student.

Keana Gorman

“[My research] really opened my eyes to the way that museums engage with Indigenous artifacts and collections from Indigenous people,” says the College alum about her research at a German museum.

Samantha Maltais

“Harvard’s origin story is inextricably intertwined to the education of Indigenous youth,” says Samantha Maltais, the first member of the Aquinnah Wampanoag tribe to enroll at the Law School.

Addressing the past

Pushing to end myth of Columbus and honor history of Indigenous peoples

Pushing to end myth of Columbus and honor history of Indigenous peoplesPeabody Museum returns sacred scrolls, pipe tomahawk to White Earth tribe

Native leaders discuss Thanksgiving, the harvest feast, and how they mark a day of loss

How educators can authentically honor and engage with Indigenous heritage and perspectives—all year long

The first delegate of a tribal nation to Congress fulfills the terms of a 185 year-old treaty

Community engagement

The annual Harvard Powwow brings Native students and others from neighboring Indigenous communities together to connect and celebrate.

Helping Native nations grow

Harvard’s Project on Indigenous Governance and Development received multiple transformational gifts to expand its long-running efforts to research, document, and share examples of effective tribal self-governance in Indigenous communities across the United States.

Addressing mental health

“We need to take seriously the Indigenous claim I hear everywhere I go in Indian country, that ‘our culture is our treatment,’” says Joseph Gone professor of global health and social medicine on the need for a return to traditional cultural practices and ritual participation instead of mainstream therapeutic activities.

Better college access for Native people

Only about 14% of Native American people attend college, and many often don’t graduate. Tarajean Yazzie-Mintz, currently the CEO of First Light Education, has spent decades trying to lower the many barriers facing Native young people as they try to access higher education.

The Native American experience

The Harvard Art Museums’ collection, assembled by the Ho Family Student Guides in collaboration with the Harvard University Native American Program, aims to elevate the voices of Indigenous peoples in the modern United States.

This land is your land

Graduate School of Design students question why “urban” and “Indigenous” are cast as opposing identities.

Growing understanding

The Graduate School of Design explores how Native American community-based farming and gardening projects are defining heirloom or heritage seeds and why maintaining and growing these seeds is so important.

In the people business

Harvard student and president and CEO of the National Center for American Indian Enterprise Development Chris James discusses the huge need for business infrastructure and entrepreneurship development in Native American communities.

Transcript

Jason Newton: Most Americans know, in a general sense, what a Native American Reservation is, and that groups of Native Americans were forced to move to them by the government of the United States throughout our country’s history.

Rachel Traughber: What you may not know is that many of these land tracts are among some of the most rural in the country – cut off from the U.S. economy and lacking in critical infrastructure and services. That reality is one factor which has led to high-poverty and limited business development opportunities for generations of Native people.

JN: Harvard Extension School student Chris James is working to change that. A former Associate Administrator at the U.S. Small Business Administration, he’s the President and CEO of the National Center for American Indian Enterprise, the largest Native American economic development organization in the United States.

RT: James has spent his life developing programs to help support the creation and growth of economic opportunity for Native Americans across the country. He joins us now to share more about his work with the National Center.

I’m Rachel Traughber, and I’m Jason Newton. And this is Unequal: a Harvard University series about race and inequality across the United States.

JN: Chris, welcome. And thank you for joining us. So I wanted to ask what drew you to working with small businesses and specifically Native American businesses?

Chris James: Well, thank you so much. You know, the biggest thing for me is I grew up in Cherokee North Carolina, on the Qualla Boundary, which is our reservation for the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. And my family for generations have had some type of small business commerce. I actually worked for my dad, in a in a small restaurant for years, my grandmother was a beader. And she had a she had a craft shop. So I, myself always had a passion for small business. And, and it was almost in my my blood. So that’s, that’s how I started working in small business. And then as I, as I continued to work on the reservation, I really got into economic development, and how can I support small businesses on the reservation was really important to me. And it just led to other opportunities in my life.

CJ: You know, there’s a huge need for business development in our Native American communities. Some of our communities are some of the most rural in United States, high poverty areas, and, and really lacks sometimes the infrastructure for business development because of the remoteness and ruralness of our communities.

JN: So you touched on the economic life on reservations all across the country, and it brings up the question for me personally, you know, can you explain some of the dynamics around what may have created such a concentration of poverty on Native reservations?

CJ: There has been hundreds and hundreds of years of relocation for our tribal communities. So for example, you know, a lot of the southeast tribes, majority of the southeast tribes were removed during the removal act in the 1800s. When those communities were moved from their existing homelands, oftentimes, they were put in a reservation community in an environment that they did not understand or even know. And it could be hundreds and hundreds of miles away from from their traditional homelands. So the traditional hunting and the traditional farming and all the things that that community had done for thousands and thousands of years, all of a sudden, that community is in a totally different environment, with totally different land and totally different types of hunting and environments. So that I think started it.

A second piece of that is the reservation system were often in very rural areas. So the ruralness, the isolation was also a factor to to high poverty in in those areas.

And then lastly, a lot of those communities were totally reliant on federal government. And unfortunately, with the overload over reliance on the federal government, there wasn’t the infrastructure development to foster businesses and to to create a system of entrepreneurship and communities.

Now, a lot of that is changing. And it has been changing for the past 20 to 30 years. Part of that is, is some of our communities, not only develop gaming enterprises, but they developed other types of business enterprises that actually support economic development and support their community. And then second, over the past 20 or 30 years, there’s also been increase support for entrepreneurship development. And organizations like myself, we really focus on that individual entrepreneur, helping them develop businesses and create jobs in the community and, and really foster an environment of success. And we also help the tribes do the same. What type of businesses can a tribe create, to, to help support the community and help bring in not only revenue for the community, but also jobs.

RT: You’re president and CEO of the National Center for American Indian Enterprise Development. Tell us a little bit about the Center. What is it and how did you become involved?

CJ: The National Center is a nonprofit organization that focuses on business enterprise development in Native American communities. The Center’s been around since 1969. It’s a 50-year-old organization. And really, it has supported billions of dollars worth of contracts to Native American businesses, including tribally owned businesses, through various types of procurement. We’ve also helped foster an ecosystem of entrepreneurship through training and technical assistance to our Native American business owners. And we’ve also supported thousands and thousands of job creation in Indian Country.

My involvement of the National Center was that I left the federal government in 2016. And and I left Washington DC, with the desire to get back to my roots. And my roots were what is economic development in Native American communities. So I felt like I could help continue the growth of the National Center. I laid out a five-year strategic plan to really focus on those core core tasks of developing businesses. We also started focusing on access to capital, and we’ve developed a Native CDFI that launches this year. And we really bolster a pipeline to support Native youth so that they can be prepared to start businesses when they’re ready. We also work with Fortune 500 companies, to help with their supply chains, and to bring in more Native American businesses in their supply chain, or into their workforce.

RT: Chris, I’m wondering if you could share with us what are some of the unique challenges that come with running a business on a reservation?

CJ: You know, Rachel, I think some of the unique challenges of running a business on a reservation is one, oftentimes, because of the overall remoteness of our reservation communities. You know, there’s, there’s not the normal commerce, like oftentimes, there’s no banking, you know, there’s, there’s no, if you need to get supplies, there’s not a Costco for your business. So a lot of times, just overall distance is a hindrance, you may have to drive two to three hours to get to a more urban market.

Last week, I was in rural Alaska. And I was in a village called Kiana, and Kiana is north of the Arctic Circle. It’s a village of about 300 people, the only way into the village is, is by plane. And the overall infrastructure and a community like that, how do you do commerce? How do you even get goods? You know, the closest bank is 1000 miles away. So how do you? How do you do commerce? And, and I think that, that leads to some unique, unique challenges, but also a wait, you know, out of the box, thinking of how to build and grow businesses in rural American and reservation and rural communities. So, you know, the unique the unique challenges are infrastructure, the banking system, sometimes lack of technology or internet, and then even sometimes lack of a workforce, or even customers.

RT: So Chris, you know, the story about you going to Alaska and being close to the Arctic Circle really brings home to me the understanding that there is a wide variety of tribal nations that you have to work with on a regular basis. You know, there are 574 federally recognized sovereign tribal nations across the United States. Each has their own custom, their own culture, their own economic needs, given this variety, this diversity, the fact that they’re so specific to their locations, and those different needs, how do you approach creating or customizing programs at a national level that can reach as many people as possible?

CJ: Rachel, that’s a great question and and the National Center we spend a lot of time listening to our community members and our business owners to try to understand the unique situations we have. We have clients from Alaska all the way to Florida, all the way to New York. And each one of those clients they do, they, they are like you, like you said, you know, they’re they’re all different different communities, different infrastructure. So possibly working with a community in Alaska is is very different than working with a community in Oklahoma. And and those businesses are often different as well. So our general approach is, you know, developing us a system, where we’re able to provide a lot of individual support. So we don’t really have, you know, we don’t do like a one fit all approach. Every time we develop a program, we run training programs, every month, we do webinars every other week, we customize that program for that particular community or that particular state, even oftentimes. So when we do a training in Alaska, it’s very customized to Alaska, and we do our own research and our own listening sessions, so that we meet the needs of the businesses in that community. So we’ve done, we did an event in the Carolinas, also about a month ago. And again, those needs of those businesses and what type of training those businesses wanted, was very different than what we’ve done in Northern California. So making sure that we listen, and then help develop a program that those those businesses are those tribes, you know, will be, will be very beneficial, helping them helping develop a program that’s very beneficial to the community.

JN: So you touched on, you know, some of the various challenges, you know, that affects what may or may not be successful. Can you maybe point to some of the success stories, like what types of businesses are successful, or sustainable in terms of revenue?

CJ: There’s thousands of different types of businesses out there that the tribes themselves have created to help bolster economic development, that also includes the gaming industry. But surprisingly, the gaming industry is a very small percentage of, of overall revenue, a very small percentage of the tribes actually rely on gaming, probably about 80% of the tribes actually have to have some other type of revenue in their communities.

Secondly, for the entrepreneurs, they’ve created businesses, from large construction companies to hospitality and retail, to arts and entertainment type businesses as well. So there, there are hundreds of different types of businesses on reservation communities, and a lot of those businesses are really doing well. Of course, COVID, has taken a huge impact in our communities all over the United States, but specifically in Native American communities, but our businesses are resilient. And, and they, you know, they are looking to grow and change and, and, you know, build economies in their community.

JN: That actually touches on a question that I wanted to bring up, you know, you mentioned COVID-19, and how it dramatically affected businesses on reservations, you know, businesses in the United States and globally, have also been affected drastically by the pandemic. So the businesses that you support, how did they fare overall throughout the pandemic? And and what’s the method of recovery from, from this as we start to hopefully, pull out of the pandemic for good?

CJ: Yeah, well, you know, we definitely can’t gloss over the realities of what COVID has done. all over the United States, but specifically in Indian Country. Nationwide, our casinos, a lot of our casinos closed their doors, oftentimes, in in many of those areas, that was the only employer. You know, the casino was one of the only employer not only for the reservation community, but also the trickle effect surrounding communities. And so you’re talking about almost a billion dollars, just in lost wages, from having the casino revenue closed up. So that that revenue when the businesses are closing, and then the tribal businesses are closing, that means that there’s a loss of jobs, a loss of of tax revenue in some areas. You know, and just, you know, just a lot of loss because of that one particular business.

For our small businesses, the National Center partnered with the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis to do a business survey, and this was about a year ago. So a lot of the businesses and the businesses are still struggling, but about 68% of our businesses have seen at least a 20 to 40% revenue reduction nationwide. And then also, for that revenue for those tribally owned businesses, some of those tribally owned businesses have had an 80% loss and that is you Mainly because of just just closures.

So you can see that that that impact. You know, we all of us see the impact throughout the United States, I mean, everything that we do every day. But then if you add the, you know, rural community, if you add high poverty in, in these areas, that impact is, is even higher. And, and some of those businesses are really small, small businesses. In fact, we found, like one in six businesses have said that they are just not even able to get back open. And that is something that the National Center has really been working hard on how can we help our businesses diversify? And how can we help them get back in operation, and what other support is out there to keep those businesses going? So we did a lot of support on on PPP programs in the SBA restaurant revitalization program. So a lot of like, information, and helping our clients apply for those funding sources.

RT: That actually leads me into my next question for you, which is, how can people listening today be supportive of native business?

CJ: I think, you know, folks that are listening today really need to understand the diversity of, of what our native communities are. And, and actually, there are a lot of opportunities for those companies, you know, for people to you know, diversify their workforce and diversify their supply chains and add more vendors that are from the Native American communities. We have so many businesses that are not only doing government contracting, but they’re working with with large companies like Lockheed Martin and Boeing. So, you know, there’s a lot of opportunities, folks should not forget that, that Native American businesses are out there. And that they’re very, they’re very diversified businesses.

A second piece is, you know, there’s lots of opportunity to make impact investments into the Native American community. That could be looking at opportunities directly supporting Native community development, financial institutions, that could be looking for opportunities to, you know, connect with an actual tribal enterprise, and, and develop the commerce on a reservation.

And then lastly, there’s also the ability to have mentors and leadership development. So folks that that might be listening to this, there’s those type of opportunities. They can reach out to organizations like myself and say, How can we support if we want to be a mentor? Or maybe we have, you know, a curriculum development to help support businesses? How can we how can we donate some of our time to help support Native American infrastructure? There’s lots of nonprofits out there like myself that that, you know that that can be a resource for your listeners.

JN: That was Harvard Extension School student Chris James, President and CEO of the National Center for American Indian Enterprise Development.

RT: If you liked what you heard, and want to learn more about Harvard’s Unequal project, visit us online at harvard.edu/unequal.

Story of Igiugig

Harvard Kennedy School alum Patrick Lynch partnered with Indigenous filmmakers to tell the story of native sovereignty in Alaska.

Read more from the Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation

The sky’s the limit

London Vallery is documenting the important role of Indigenous astronomy within her community and working to improve Indigenous representation in aerospace.

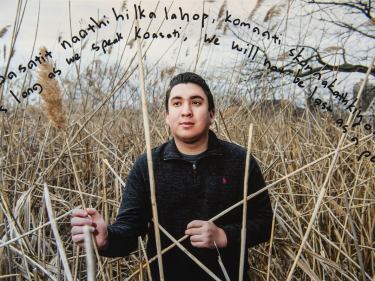

Preserving language

The Yuchi Language Project and indigenous identity

The Yuchi Language Project and indigenous identityBefore graduating to work with Teach for America, Eli Langley became the first tribal member to use their Native language to fulfill the College’s second language requirement.

Sadada Jackson, a member of the Nipmuc tribe and Divinity School alum, curated an exhibit of indigenous-language.