Poetry

Poetry at Harvard

Harvard is dedicated to exploring the history and inspiring the future of this vital art form through readings, courses, collections, and resources.

National Youth Poet Laureate

Alyssa Gaines

Like many first-years, Alyssa Gaines, the 2022 U.S. National Youth Poet Laureate, wasted no time immersing herself in campus life. In addition to continuing to explore the art of poetry, she starred in a production of “In the Heights” and will be the first Black musical director of the first-year musical.

Woodberry Poetry Room

With over 5,000 recordings on a range of media that span the 20th and 21st centuries, the Poetry Room invites you to explore one of the largest archives of literary recordings in America.

Highlights from the Listening Booth

The Listening Booth is a digital audio archive featuring highlights from the Woodberry Poetry Room, one of the largest repositories for literary recordings in the country. We welcome you to sample this selection or explore the Listening Booth itself, with readings by W. H. Auden, Amiri Baraka, Elizabeth Bishop, Jorge Luis Borges, E. E. Cummings, Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Claudia Rankine, Adrienne Rich, Dylan Thomas, Wallace Stevens, and more. For recent recordings, visit the Poetry Room’s YouTube channel.

Transcripts

(SINGING) “Nobody knows the trouble I seen. Nobody knows.”

“Wise 1. If you ever find yourself somewhere lost and surrounded by enemies who won’t let you speak in your own language, who destroy your statues and instruments, who ban your oom boom ba boom, then you are in trouble. Deep trouble. They ban your oom boom ba boom, you in deep, deep trouble. Probably take you several hundred years to get out.”

Elizabeth Bishop, “In the Waiting Room” (1976)

This poem is called “In the Waiting Room.”

“In Worcester, Massachusetts, I went with Aunt Consuelo to keep her dentist appointment. Sat and waited for her in the dentist’s waiting room. It was winter. It got dark early.

The waiting room was full of grown-up people, arctics and overcoats, lamps, and magazines. My aunt was inside what seemed like a long time. And while I waited, I read The National Geographic. I could read. And carefully studied the photographs. The inside of a volcano, black and full of ashes. Then it was spilling over in rivulets of fire. Osa and Martin Johnson dressed in riding breeches, laced boots and pith helmets. A dead man slung on a pole—‘Long Pig’ the caption said.

Babies with pointed heads wound round and round with string. Black naked women with necks wound round and round with wire, like the necks of light bulbs. Their breasts were horrifying. I read it right straight through. I was too shy to stop.

And then I looked at the cover, the yellow margins, the date. Suddenly, from inside came and ‘Oh’ of pain– Aunt Consuelo’s voice. Not very loud or long. I wasn’t at all surprised. Even then I knew she was a foolish, timid woman.

I might have been embarrassed, but wasn’t. What took me completely by surprise was that it was me, my voice and my mouth. Without thinking at all, I was my foolish aunt. I, we, were falling, falling. Our eyes glued to the cover of The National Geographic, February 1918.

I said to myself, three days and you’ll be seven years old. I was saying it to stop the sensation of falling off the round, turning world into cold, blue-black space. But I felt: you are an I. You are an Elizabeth. You’re one of them. Why should you be one too?

I scarcely dared to look to see what it was I was. I gave a sidelong glance. I couldn’t look any higher at shadowy gray knees, trousers, and skirts, and boots, and different pairs of hands lying under the lamps.

I knew that nothing stranger had ever happened. Nothing stranger could ever happen. Why should I be my aunt, or me, or anyone? What similarities– boots, hands, the family voice that I felt in my throat, or even National Geographic and those awful hanging breasts held us all together or made us all just one. How– I didn’t know any word for it–

how unlikely. How did I come to be here, like them? And over here, a cry of pain that could have got loud and worse, but hadn’t.

The waiting room was bright and too hot. It was sliding beneath the big black wave, another and another. Then I was back in it. The war was on. Outside, in Worcester, Massachusetts, were night, and slush, and cold. And it was still the 5th of February, 1918.”

[APPLAUSE]

Natalie Diaz, “American Arithmetic” (2020)

“American Arithmetic. Native Americans make up less than 1% of the population of America, 0.8% of 100%. Oh mine efficient country. I do not remember the days before America. I do not remember the days when we were all here.

Police kill Native Americans more than any other race. Race is a funny word. Race implies someone will win, implies I have as good a chance of winning as– who wins the race that isn’t a race?

Native Americans make up 1.9% of all police killings, higher per capita than any race. Sometimes race means run. I’m not good at math. Can you blame me? I’ve had an American education. We are Americans, and we are less than 1% of Americans. We do a better job of dying by police than we do existing. When we are dying, who should we call, the police, or our senator? Please, someone call my mother.

At the National Museum of the American Indian, 68% of the collection is from the United States. I am doing my best to not become a museum of myself. I am doing my best to breathe in and out. I am begging, let me be lonely, but not invisible.

But in an American room of 100 people I am Native American, less than one, less than whole, I am less than myself, only a fraction of a body. Let’s say I am only a hand, and when I slip it beneath the shirt of my lover, I disappear completely. Gracias.”

Robert Frost, “The Road Not Taken” (1962)

“Two roads diverged in a yellow wood, and sorry I could not travel both and be one traveler, long I stood and looked down one as far as I could to where it bent in the undergrowth, then took the other, as just as fair, and having perhaps the better claim, because it was grassy and wanted wear, there as for that the passing there had worn them really about the same, and both that morning equally lay in leaves no step had trodden black.

Oh, I kept the first for another day! Yet knowing how way leads on to way, I doubted if I should ever come back. I shall be telling this with a sigh somewhere ages and ages hence, two roads diverged in a wood, and I– I took the one less traveled by, and that has made all the difference.

Good night.”

Allen Ginsberg (and the Fugs), “Do the Meditation Rock “(1986)

“Do the Meditation Rock: Instructions for Sitting Practice of Meditation.” [MUSIC]

“If you want to learn how to meditate I’ll tell you how, cause it’s never too late. I’ll tell you how cause I can’t wait. It’s just that great that it’s never too late.

If you are an old fraud like me or a lama who lives in eternity, the first thing you do when you meditate is keep your spine, your backbone straight. Sit yourself down on a pillow on the ground or sit in a chair if the ground isn’t there, if the ground isn’t there, if the ground isn’t there, sit where you are if the ground isn’t there.

Do the meditation, do the meditation, do the meditation, do the meditation. Learn a little patience and generosity.

[MUSIC]

I fought the Dharma and the Dharma won. [MUSIC]

Follow your breath out, open your eyes. Sit there steady and sit there wise. Follow your breath right out of your nose, follow it out wherever it goes. Follow your breath, but don’t hang on to the thought of your death in old Saigon.

Follow your breath. When thought-forms rise, whatever you think, it’s a big surprise. It’s a big surprise. It’s a big surprise. Whatever you think, it’s a big surprise. Do the meditation. Do the meditation. Do the meditation. Do the meditation. Learn a little patience and generosity generosity generosity generosity yeah generosity. [MUSIC]

All you’ve got to do is to imitate. You’re sitting meditating and it’s never too late. When thoughts catch up but your breath goes on, you don’t have to drop your nuclear bomb. boom boom boom boom bum boom-boom boom boom ba-boom-ba ba boom-boom boom.

If you see a vision come, say hello, goodbye. You can go with your only eye. When you see a holocaust, you can reverse your mind. It just went fast with the winter wind.

Do the meditation, do the meditation. Do the meditation. Do the meditation. Learn a little patience and generosity. duh-duh duh-duh duh-duh duh-duh-duh dum-da-dum Learn a little patience and generosity.

When you see apocalypse in a long red car or a flying saucer, sit where you are. If you feel a little bliss, don’t worry about that. Give your wife a kiss when your tire goes flat. When your tire goes flat, when your tire goes flat, keep your hard-on under your hat.

If you can’t think straight and you don’t know who to call, it’s never too late to do nothing at all. Do nothing at all. Do nothing at all. It’s never too late to do nothing at all.

Do the meditation, follow your breath, so your body and your mind get together for a rest. Get together for a rest, get together for a rest. Relax your mind, get together for a rest.

Do the meditation, do the meditation, do the meditation, do the meditation. Learn a little patience and generosity, generosity, generosity, generosity, yeah generosity. [MUSIC]

If you sit for an hour or a minute every day, you can tell the superpower to sit the same way. You can tell the superpower to watch and to wait. And there’s nothing that’ll take ya. Never too late. It’s never too late. It’s never too late to tell the superpower to stop and meditate. No, it’s never too late. It’s never too late to tell the superpower to stop and meditate.

Do the meditation, do the meditation, do the meditation, do the meditation. Learn a little patience and generosity.

Get yourself together lots of energy and learn a little patience and generosity. Generosity, generosity, generosity, yeah, generosity.

Do the meditation, do the meditation, do the meditation, do the meditation. Learn a little patience and generosity. Generosity, generosity, generosity, yeah generosity, generosity, generosity, generosity, yeah generosity.” [APPLAUSE]

Amanda Gorman, “Note” and “Old Jim Crow Got to Go” (2020)

“I’m only going to read two poems and they’re actually quite short. And the reason I’m reading them and keeping them brief is because they actually come from very long histories, which I would love to talk about today since it’s my favorite month, Black History Month. Woo! Woo! So I thought I’d talk about Black people and Black history.

The first poem I’m going to read is actually an erasure poem. And it concerns Phillis Wheatley, who, if you didn’t know, was the first African-American to publish a book of poetry. She was actually an African slave who was brought here to Massachusetts, Boston, actually, around the age of– from the records, people are guessing eight or nine, and around the age of 12 she actually started publishing poetry.

Keep in mind that she had come to the States without speaking any English. And by the time she was younger than me she could read the classics, she could read Latin, she was publishing in her work. Now, this brought forth a very interesting question for the white supremacist structure that was organizing at that time which is to say, how can this young, skinny, sickly-looking, black teenager be writing these poems?

To the point that she was actually brought to a tribunal in front of 18 white men, many of whom were graduates of this very university, so they could interrogate her and see if she actually had authored her poems. We don’t know what happened in the room where it happened, but we know that by the time she left that space she had come out with a declaration signed by the 18 intellectuals at the time saying she indeed had authored her poems.

This was not enough, though, for someone by the name of Thomas Jefferson, who, in 1785 published what’s called Notes on the State of Virginia. And the idea that a founding father who was then running a slave state would dedicate part of his treatise on slavery to addressing a black female slave was incredible. To the point that he had to say, I cannot defend slavery unless I can prove that Phillis Wheatley’s credit does not count.

And so I decided to look to Notes on the State of Virginia and erase some of Thomas Jefferson’s words in the same way that he erased the contributions of Phillis Wheatley. So this is an eraser poem of the paragraph in which he addresses Phillis.

But I find a black above narration. See an elementary trait of painting, or sculpture, more generally whites with accurate ears have been found capable of imagining. Whether they will be the composition of a more extensive composition is complicated and yet to be proved. Often, most poetry is misery enough. God knows no poetry. Love the poets. Their love is ardent. Its senses only imagination. Indeed, a Phillis Wheatley, a poet, published under her name, dignity.

I’m going to read a second poem. And this one I wrote– I want to say freshman year. Wow, throw back! And it was when The New York Times asked me to write a coda to Black History Month. And I remember that fall kind of running around campus pulling my hair out because I had no idea how I was supposed to say something new about race relations or blackness.

And finally, I kind of sat down to myself and I realized I don’t necessarily need to say something new. I think I should actually say something old that should be heard, and listened to, internalized yet again. So I looked to the archives at the National Museum of African-American History and Culture– long title– that’s in DC, and they have all of these protest flyers, and pins, and posters that have incredible text on it. The words, and the language, and the rhetoric of a movement.

And so we closed all of the flyers that I could find that were engaged with these ideas of protest and freedom. And I composed those into a poem. So I don’t necessarily consider it really my poem, but more so a poem that’s calling forth on the language of what created the freedom that I get to exist is today. It’s called “Old Jim Crow Got to Go.”

Whose face is white as snow, everywhere Daisy goes no dogs, no Negro, I am a man. I am the way I am. I look the way I look, I am my age. Black power core Malcolm X speaks for me. He died to make men free. Malcolm’s legacy, one man, one vote, SNCC, don’t you want to be free?

I’m for King’s Way, watch your backs cooking and smoking. Where we at? Black males, an endangered species, a perspective on solidarity. Black is beautiful. Free Angela Davis liberation in the making. Angela’s free. Free all political prisoners. 50% black woman artist revolutionary hope.

Shirley Chisolm, unbiased and nought anatomy of the black aesthetic. An examination. Nikki Giovanni, poet, critic. Go home. Harriet Tubman, home. She allegedly has purchased several guns in the past. Consider possibly armed and dangerous.

I believe Anita Hill, age 26, height 5′ 8″, hair black, occupation, teacher. Small scars on both knees, race, Negro, nationality, American. Woman. Free. Our sisters, what can a girl do? What have women done? What can you do? End racism and suppression.

Testimony from a black sister marks the beginning in the hearts and the lives of all black men and women. Get it together. We march with Selma, we march through Montgomery. The moonwalk won’t be as bad as our walk. Move on over.

We’ll move on over you, lifting as we climb. We shall overcome. Freedom, ride core. Keep us flying, keep us flying. Don’t you want to be free? Liberty and equality, they shall not die.”

Seamus Heaney, “Villanelle for an Anniversary” (1986)

“The atom lay unsplit, the west unwon,

The books stood open and the gates unbarred.

The maps dreamt on like moondust. Nothing stirred.

The future was a verb in hibernation.

A spirit moved, John Harvard walked the yard.

Before the classic style, before the clapboard,

All through the small hours of an origin,

The books stood open and the gate unbarred.

Night passage of a migratory bird.

Wingflap. Gownflap. Like a homing pigeon

A spirit moved, John Harvard walked the yard.

Was that his soul (look) sped to its reward

By grace or works? A shooting star? An omen?

The books stood open and the gate unbarred.

Begin again where frosts and tests were hard.

Find yourself or founder. Here, imagine

A spirit moves, John Harvard walks the yard,

The books stand open and the gates unbarred.”

Robert Lowell, “Skunk Hour” (1958)

“Skunk Hour.”

“Nautilus Island’s hermit heiress still lives through winter in her Spartan cottage; Her sheep still graze above the sea. Her son’s a bishop. Her farmer is first selectman in our village; she’s in her dotage.

Thirsting for the hierarchic privacy of Queen Victoria’s century, she buys up all the eyesores facing her shore, and lets them fall. The season’s ill– we’ve lost our summer millionaire, who seemed to leap from an LL Bean catalog. His nine-knot yawl was auctioned off to lobstermen.

A red fox stain covers Blue Hill. And now our fairy decorator brightens his shop for fall; his fishnet’s filled with orange cork, orange his cobbler’s bench and awl; there is no money in his work, he’d rather marry. One dark night, my Tudor Ford—”

That’s spelled T-U-D-O-R and means “two doors”—

“One dark night, my Tudor Ford climbed the hill’s skull; I watched for love cars. Lights turned down, they lay together, hull to hull, where the graveyard shelves on the town. My mind’s not right.

A car radio bleats, ‘Love, O careless Love.’ I hear my ill spirit sob in each blood cell, as if my hand were at its throat. I myself am hell; nobody’s here– only skunks, that search in the moonlight for a bite to eat. They march on their soles up Main Street: white stripes, moonstruck eyes’ red fire under the chalk-dry and spar spire of the Trinitarian Church. I stand on top of our back steps and breathe the rich air– a mother skunk with her column of kittens swills the garbage pail. She jabs her wedge-head in a cup of sour cream, drops her ostrich tail, and will not scare.”

Claudia Rankine, “Making Room” (2015)

“We had a very interesting discussion about what it means to recognize a break in American society and how you then address it. Obviously, you vote. But then you also put your body in that place.

On the train, the woman standing makes you understand there are no seats available. And in fact, there is one. Is the woman getting off in the next stop? No. She would rather stand all the way to Union Station. The space next to the man is the pause in a conversation you are suddenly rushing to fill. You step quickly over the woman’s fear, a fear she shares. You let her have it.

The man doesn’t acknowledge you as you sit down because the man knows more about the unoccupied seat than you do. For him, you imagine it is more like breath than wonder. He has had to think about it so much, you wouldn’t call it thought. When another passenger leaves his seat and the standing woman sits, you glance over at the man. He’s gazing out the window into what looks like darkness.

You sit next to the man on the train, bus, in the plane, waiting room, anywhere he could be forsaken. You put your body there in proximity to, adjacent to, alongside. You don’t speak unless you are spoken to, and your body speaks to the space you fill. And you keep trying to fill it, except the space belongs to the body of the man next to you, not to you.

Where he goes, the space follows him. If the man left his seat before Union Station, you would simply be a person in a seat on the train. You would cease to struggle against the unoccupied seat. When, where, why? The space won’t lose its meaning. You imagine if the man spoke to you, he would say, it’s OK. I’m OK. You don’t need to sit here. You don’t need to sit.

And you sit and look past him. Into the darkness, the train is moving through a tunnel. All the while, the darkness allows you to look at him. Does he feel you looking at him? You suspect so. What does suspicion mean? What does suspicion do? The soft gray-green of your cotton coat touches the sleeve of him. You are shoulder to shoulder though standing you could feel shadowed. You sit to repair whom, who.

You erase that thought, and it might be too late for that. It might forever be too late or too early. The train moves too fast for your eyes to adjust to anything beyond the man, the window, the tiled tunnel, its slick darkness. Occasionally, a white light flickers by like a displaced sound.

From across the aisle tracks room harbor world, a woman asks a man in the rows ahead if he would mind switching seats. She wishes to sit with her daughter or son. You hear, but you don’t hear. You can’t see. It’s then the man next to you turns to you. And as if from inside your own head, you agree that if anyone asks you to move, you’ll tell them, we are traveling as a family.”

Adrienne Rich, “For the Felling of an Elm in Harvard Yard” (1951)

“For the Felling of an Elm in the Harvard Yard.”

“They say the ground precisely swept, no longer feeds with rich decay the roots enormous in their age, that long and deep beneath have slept. So the great spire is overthrown, and sharp saws have gone hurtling through the rings that three slow centuries wore; The second oldest elm is down.

The shade where James and Whitehead strolled becomes a litter on the green. The young men pause along the paths to see the axes glinting bold. Watching the hewn trunk dragged away, some turn the symbol to their own, and some admire the clean dispatch with which the aged elm came down.”

Mary Ruefle, “Short Lecture on Shakespeare” (2013)

“Short lecture on Shakespeare.”

“They say there are no known facts about Shakespeare because if it were his pen name, as many believe, then whom that bed was willed to is a moot point. Yet, there is one hard, cold, clear fact about him, a fact that freezes the mind that dares to contemplate it. In the beginning, William Shakespeare was a baby and knew absolutely nothing. He couldn’t even speak.”

Wallace Stevens, “Final Soliloquy of the Interior Paramour” (1952)

“Light the first light of evening, as in a room in which we rest, and, for small reason, think the world imagined is the ultimate good. This is, therefore, the intensest rendezvous. It is in that thought that we collect ourselves, out of all the indifferences, into one thing. Within a single thing, a single shawl wrapped tightly round us, since we are poor, a warmth, a light, a power, the miraculous influence.

Here, now, we forget each other and ourselves. We feel the obscurity of an order, a whole, a knowledge, that which arranged the rendezvous. Within its vital boundary, in the mind. We say God and the imagination are one. How high that highest candle lights the dark. Out of this same light, out of the central mind, we make a dwelling in the evening in which being there together is enough.

That’s all.”

[APPLAUSE]

Ocean Vuong, “Not Even This” (2020)

“Hey, I used to be a fag, now I’m a checkbox. The pen tip jabbed in my back, I feel the mark of progress.

I will not dance alone in the municipal graveyard at midnight, blasting sad songs on my phone for nothing. I promise you, I was here. I felt things that made death so large it was indistinguishable from air, and I went on destroying inside it like wind in a storm.

The way Little Peep says, I’ll be back in the morning, when you know how it ends. The way I kept dancing when the song was over, because it freed me. The way the street light blinks once before waking up for its night shift like we do. The way we look up and whisper sorry to each other. The boy and I, when there’s teeth, when there’s always teeth on purpose. When I throw myself into gravity and made it work, ha.

I made it out by the skin of my griefs. I used to be a fag, now I’m lit, ha. Once, at a party set on a rooftop in Brooklyn for an artsy vibe, a young woman said, sipping her drink, you’re so lucky you’re gay. Plus you get to write about war and stuff. I’m just white. Pause. I got.

[LAUGHTER]

Pause. I got nothing. Laughter, glasses clinking. Unlike feelings, blood gets realer when you feel it, because everyone knows yellow pain pressed into American letters turns to gold.

Our sorrow, Midas touched napalm with a rainbow afterglow. I’m trying to be real, but it costs too much. They say the Earth spins, and that’s why we fall, but everyone knows it’s the music. It’s been proven difficult to dance to machine gun fire. Still, my people made a rhythm this way.

Away, my people so still in the photographs, as corpses. My failure was that I got used to it. I looked at us, mangled under the time photographer’s shadow and stopped thinking, get up. Get up. I saw the graveyard steam in the pinkish dawn, and knew the dead were still breathing, ha.

If they come from me, take me out. What if it wasn’t the crash that made me, but the debris? What if it was meant this way, the mother, the lexicon, the line of cocaine on the Mohawk boy’s collarbone in an East Village sublet in 2007? What’s wrong with me, doc? There must be a pill for this.

Too late. These words already shrapnel in your brain. Impossible in high school, I am now the ultimate linebacker. I plow through the page, making a path for you, dear reader, going nowhere, because the fairy tales were right. You’ll need magic to make it out of here.

Long ago, in another life, on an Amtrak through Iowa, I saw for a few blurred seconds a man standing in the middle of a field of winter grass, hands at his side, back to me, all of him stopped there, save for his hair scraped low by wind. When the countryside resumed its wash of gray wheat, tractors, gutted barns, black sycamores and herdless pastures, I started to cry.

I put my copy of Didion’s The White Album down and folded a new dark around my head. The woman beside me stroked my back, saying in a Midwestern accent that wobbled with tenderness, go on son. You get that out now. No shame in breaking open. You get that out, and I’ll fetch us some tea, which made me lose it even more. She came back with Lipton in paper cups, her eyes nowhere blue and there. She was silent all the way to Missoula, where she got off and said, patting my knee, God is good. God is good.

I can say it was beautiful now, my harm, because it belonged to no one else. To be a dam for damage, my shittiness will not enter the world, I thought, and quickly became my own hero. Do you know how many hours I’ve wasted watching straight boys play video games?

[LAUGHTER]

Enough.

[LAUGHTER]

Time is a mother. Lest we forget, the morgue is also a community center. In my language, the one I recall now only by closing my eyes, the word for love is yeu and the word for weakness is yeu? How you say what you mean changes what you say. Some call this prayer, I call it watch your mouth.

When they zipped my mother in a body bag, I whispered, Rose, get out of there, your plants are dying. Enough is enough. Body, doorway that you are, be more than what I’ll pass through.

Stillness, that’s what it was. The man in the field in the red sweater. He was so still he became somehow more true, like a knife wound in a landscape painting. Like him, I caved. I caved and decided it will be joy from now on. Then everything opened. The lights blazed around me into a white weather, and I was lifted, wet and bloody, out of my mother, screaming and enough.”

William Carlos Williams, “Spring and All” and “This Is Just to Say” (1951)

“By the road to the contagious hospital under the surge of the blue mottled clouds driven from the northeast, a cold wind. Beyond, the waste of broad muddy fields brown with dried weeds, standing and fallen. Patches of standing water, the scattering of tall trees. All along the road the reddish purplish, forked, upstanding, twiggy stuff of bushes and small trees, with dead, brown leaves under them, leafless vines. Lifeless in appearance, sluggish dazed spring approaches. They enter the new world naked, cold, uncertain of all save that they enter. All about them the cold, familiar wind.

Now the grass, tomorrow the stiff curl of wildcarrot leaf. One by one objects are defined. It quickens, clarity, outline of leaf, but now the stark dignity of entrance. Still the profound change has come upon them. Rooted, they grip down and begin to awaken.”

And this one, I think, has been used for teaching.

[LAUGHTER]

Modern American poetry is like a man without a head. We’ve got the whole body of English literature right there. All that we need is a head, that’s all.

“This is just to say I have eaten the plums that were in the icebox and which you were probably saving for breakfast. Forgive me. They were delicious, so sweet and so cold.”

Let me read it again.

[LAUGHTER]

“This is just to say I have eaten the plums that were in the icebox and which you were probably saving for breakfast. Forgive me. They were delicious, so sweet and so cold.”

I’ve been psychoanalyzed.

[LAUGHTER]

I think someone, I won’t mention his name, who ah, the secret of Dr. Williams is in the last line. “And so cold.”

[LAUGHTER]

Well, I have some ideas on that too, but we won’t talk about them here.

T. S. Eliot’s First Harvard recording

As the country’s first library of voices, the Woodberry Poetry Room helped create some of the earliest recordings of such writers as Ralph Ellison, Robert Frost, Audre Lorde, Vladimir Nabokov, Sylvia Plath, and T. S. Eliot. We invite you to listen to one of the most rare recordings in the archive: T. S. Eliot’s first known poetry recording—produced at Harvard in 1933 and re-released as a Harvard Vocarium LP in 1951. With thanks to the Eliot Foundation for their generous permission.

Transcripts

“The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.”

Let us go then, you and I, when the evening is spread out against the sky like patient etherized upon a table. Let us go through certain half-deserted streets, the muttering retreats of restless nights in one-night cheap hotels and sawdust restaurants with oyster shells. Streets that follow like a tedious argument of insidious intent to lead you to an overwhelming question– Oh, do not ask, what is it? Let us go and make our visit. In the room, the women come and go talking of Michelangelo.

The yellow fog that rubs its back upon the window panes. The yellow smoke that rubs its muzzle on the window panes. Licked its tongue into the corners of the evening, lingered upon the pools that stand in drains. Let fall upon its back the soot that falls from chimneys. Slipped by the terrace, made a sudden leap. And seeing that it was a soft October night, curled once about the house and fell asleep.

And indeed there will be time for the yellow smoke that slides along the street rubbing its back upon the window panes. There will be time, there will be time to prepare a face to meet the faces that you meet.

There will be time to murder and create, and time for all the works and days of hands that lift and drop a question on your plate. Time for you and time for me, and time yet for a hundred indecisions and for a hundred visions and revisions before the taking of a toast and tea. In the room, the women come and go talking of Michelangelo.

And indeed, there will be time to wonder, do I dare, and do I dare? Time to turn back and descend the stair with a bald spot in the middle of my hair. They will say, how his hair is growing thin. My morning coat, my collar mounting firmly to the chin. My necktie rich and modest but asserted by a simple pin. They will say, but how his arms and legs are thin. Do I dare disturb the universe?

In a minute, there is time for decisions and revisions which a minute will reverse. For I have known them all already, known them all. Have known the evenings, mornings, afternoons. I have measured out my life with coffee spoons. I know the voices dying with a dying fall beneath the music from a farther room. So how should I presume?

And I have known the eyes already, known them all, the eyes that fix you in a formulated phrase. And when I am formulated, sprawling on a pin. When I am pinned and wriggling on the wall, then how should I begin to spit out all the butt-ends of my days and ways? And how should I presume?

And I have known the arms already, known them all, arms that are braceleted and white and bare. But in the lamplight, downed with light brown hair, is it perfume from a dress that makes me so digress? Arms that lie along a table or wrap about a shawl. And how should I presume? And how should I begin?

Shall I say, I have gone at dusk through narrow streets and watched the smoke that rises from the pipes of lonely men in shirtsleeves leaning out of windows. I should have been a pair of ragged claws scuttling across the floors of silent seas. And the afternoon, the evening, sleeps so peacefully smoothed by long fingers. Asleep, tired, or it malingers stretched on the floor here beside you and me.

Should I, after tea and cakes and ices, have the strength to force the moment to its crisis? But though I have wept and fasted, wept and prayed. Though I have seen my head grown slightly bald brought in upon

a platter. I am no prophet, and here’s no great matter. I have seen the moment of my greatness flicker, and I have seen the eternal footman hold my coat and snicker. And in short, I was afraid.

And would it have been worth it, after all, after the cups, the marmalade, the tea, among the porcelain, among some talk of you and me? Would it have been worthwhile to have bitten off the matter with a smile? To have squeezed the universe into a ball to roll it towards some overwhelming question. To say, I am Lazarus, come from the dead, come back to tell you all, I shall tell you all– if one, settling a pillow by her head, should say, that is not what I meant at all.

That is not it at all.

And would it have been worth it after all? Would it have been worthwhile after the sunsets and the dooryards and the sprinkled streets? After the novels, after the teacups, after the skirts that trail along the floor, and this, and so much more? It is impossible to say just what I mean!

But as if a magic lantern through the nerves in patterns on a screen. Would it have been worthwhile if one, settling a pillow or throwing off a shawl and turning toward the window, should say, that is not it at all. That is not what I meant at all.

No, I am not Prince Hamlet, nor was meant to be. Am an attendant lord, one that will do to swell a progress, start the scene or two, advise the prince. No doubt an easy tool, deferential, glad to be of use, politic, cautious, and meticulous. Full of high sentence, but a bit obtuse. At times, indeed, almost ridiculous. Almost, that times, the fool.

I grow old. I grow old. I shall wear the bottoms of my trousers rolled. Shall I part my hair behind? Do I dare to eat a peach? I saw wear white flannel trousers and walk up on the beach. I have heard the mermaid singing each to each. I do not think that they will sing to me.

I have seen them riding seaward on the waves combing with white hair of the waves blown back when the wind blows the water white then black. We have lingered in the chambers of the sea by sea girls wreathed with seaweed red and brown till human voices wake us and we drown.

“Gerontion.”

Thou hast nor youth nor age, but as it were, an after dinner sleep dreaming of both. Here I am, an old man in a dry month being read to by a boy waiting for rain. I was neither at the hot gates nor fought in the warm rain nor knee deep in the salt marsh heaving a cutlass bitten by flies, fought. My house is a decayed house, and the Jew squats on the window sill, the owner spawned in some estaminet of Antwerp, blistered in Brussels, patched and peeled in London. The goat coughs at night in the field overhead. Rocks, moss, stone crop, iron, merds. The woman keeps the kitchen, makes tea, sneezes at evening, poking the peevish gutter. I, an old man, a dull head among windy spaces. Signs are taken for wonders. We would see a sign. The word within a word, unable to speak a word, swaddled with darkness. In the juvescence of the year came Christ the tiger. In depraved May, dogwood and chestnut, flowering Judas, to be eaten, to be divided, to be drunk among whispers. By Mr. Silvero with caressing hands, at Limoges who walked all night in the next room.

By Hakagawa, bowing among the Titians. By Madame de Tornquist, in the dark room shifting the candles. Fraulein von Kulp who turned in the hall, one hand on the door. Vacant shuffles weave the wind. I have no ghosts. An old man in a draughty house under a window knob.

After such knowledge, what forgiveness? Think now. History has many cunning passages, contrived corridors and issues. Deceives with whispering ambitions. Guides us by vanities. Think now. She gives when our attention is distracted, and what she gives, gives with such supple confusions that the giving famishes the craving.

Gives too late. What’s not believed in or is still believed in memory only. Reconsidered passion gives too soon. Into weak hands, what’s thought can be dispensed with till the refusal propagates a fear. Think. Neither fear nor courage saves us. Unnatural vices are fathered by our heroism. Virtues are forced upon us by our impudent crimes. These tears are shaken from the wrath-bearing three.

The tiger springs in the new year. Us he devours. Think at last. We have not reached conclusion when I stiffen in a rented house. Think at last I have not made this show purposelessly, and it is not by any concitation of the backward devils. I would meet you upon this honestly. I that was near your heart was removed therefrom to lose beauty in terror, terror in inquisition.

I have lost my passion. Why should I need to keep it since what is kept must be adulterated? I have lost my sight, smell, hearing, taste, and touch. How should I use them for your closer contact? These, with a thousand small deliberations protract the profit of their chilled delirium, excite the membrane, when the sense has cooled, with pungent sauces. Multiply variety in a wilderness of mirrors.

What will the spider do? Suspend its operations? Will the weevil delay? De Bailhache, Fresca, Mrs. Cammel, whirled beyond the circuit of the shuddering bear in fractured atoms. Gull against the wind in the windy straights of Belle Isle or running on the Horn. White feathers in the snow, the Gulf claims. And an old man, driven by the trades, to a sleepy corner. Tenants of the house. Thoughts of a dry brain in a dry season.

“The Hollow Men.”

We are the hollow men. We are the stuffed men leaning together, headpiece filled with straw. Alas. Our dried voices, when we whisper together, are quiet and meaningless as wind and dry grass or rats’ feet over broken glass in our dry cellar.

Shape without form, shade without color. Paralyzed force. Gesture without motion. Those who have crossed with direct eyes to death’s other kingdom. Remember us, if at all, not as lost, violent souls but only as the hollow men, this stuffed men.

Eyes I dare not meet in dreams. In death’s dream kingdom, these do not appear. There, the eyes are sunlight on a broken column. There is a tree swinging, and voices are in the wind singing more distant and more solemn than a fading star.

Let me be known nearer in death’s dream kingdom. Let me also wear such deliberate disguises– rat’s coats, crow skin, crossed staves in a field, behaving as the wind behaves. No nearer. Not that final meeting in the twilight kingdom.

This is the dead land. This is cactus land. Here, the stone images are raised. Here, they receive the supplication of a dead man’s hand under the twinkle of a fading star. Is it like this in death’s other kingdom? Waking alone at the hour when we are trembling with tenderness. Lips that would kiss form prayers to broken stone.

The eyes are not here. There are no eyes here in this valley of dying stars, in this hollow valley, this broken jaw of our lost kingdoms. In this last meeting places we grope together and avoid speech gathered on this beach of the tumid river. Sightless, unless the eyes reappear as the perpetual star, multifoliate rose of death’s twilight kingdom. They hope only of empty men.

Here we go round the prickly pear, prickly pear, prickly pear. Here we go round the prickly pear at 5 o’clock in the morning. Between the idea and the reality, between the motion and the act, falls the shadow. For Thine is the kingdom.

Between the conception and the creation, between the emotion and the response, falls the shadow. Life is very long. Between the desire and the spasm, between the potency and the existence, between the essence and the descent, falls the shadow. For Thine is the kingdom. For thine is– life is– for thine is the– this is the way the world ends. This is the way the world ends. This is the way the world ends. Not with a bang but a whimper.

“Triumphal March.”

Stone. bronze, stone, steel, stone, oak leaves, horses’ heels over the paving. And the flags, and the trumpets, and so many eagles. How many? Count them. And such a press of people. We hardly knew ourselves that day or knew the city.

This is the way to the temple, and we, so many, crowding the way. So many waiting. How many waiting? What did it matter on such a day? Are they coming? No, not yet. You can see some eagles and hear the trumpets. Here they come. Is he coming?

The natural wakeful life of our ego is a perceiving. We can wait with our stools and our sausages. What comes first? Can you see? Tell us. It is 5,800,000 rifles and carbons, 102,000 machine guns, 28,000 trench mortars, 53,000 field and heavy guns.

I cannot tell how many projectiles, mines, and fuses. 13,000 airplanes, 24,000 airplane engines, 50,000 ammunition wagons, now 55,000 army wagons, 11,000 field Kitchens, 1,150 field bakeries. What a time that took. Will it be he no? No. Those are the golf club captains. These, the scouts.

And now, the societe gymnastique de Poissy. And now, come the mayor and the liverymen. Look, there he is now. Look. There is no interrogation in his eyes or in the hands. Quiet over the horse’s neck. And the eyes, watchful, waiting, perceiving, indifferent. Oh, hidden under the dove’s wing, hidden in the turtle’s breast. Under the palm tree at noon. Under the running water. At the still point of the turning world. Oh, hidden.

Now they go up to the temple. Then, the sacrifice. Now come the virgins bearing urns, urns containing dust. Dust. Dust of dust. And now, stone, bronze, stone, steel, stone, oak leaves, horses’ heels over the paving.

That is all we could see. But how many eagles, and how many trumpets? And Easter Day we didn’t get to the country, so we took young Cyril to church. And they rang a bell. And he said, right out loud, crumpets. Don’t throw away that sausage. It’ll come in handy. He’s artful. Please, will you give us a light? Light. Light. Et les soldats faisaient la haie? Ils la faisaient.

“Journey of the Magi.”

A cold coming we had of it, just the worst time of the year for a journey. And such a long journey. The ways deep and the weather sharp. The very dead of winter. And the camels galled, sore-footed, refractory, lying down in the melting snow. There were times we regretted the summer palaces on slopes, the terraces, and the silken girls bringing sherbet.

Then the camel men cursing and grumbling and running away and wanting their liquor and women. And the night fires going out, and the lack of shelters, and the cities hostile and the towns unfriendly, and the villages dirty and charging high prices. A hard time we heard of it. At the end, we preferred to travel all night sleeping in snatches with the voices singing in our ears saying that this was all folly.

Then at dawn we came down to a temperate valley, wet below the snow line, smelling of vegetation, with a running stream and a water mill beating the darkness, and three trees on the low sky, and an old white horse galloping away in the meadow.

Then we came to a tavern with vine leaves over the lintel. Six hands at an open door dicing for pieces of silver, and feet kicking the empty wine skins. But there was no information. And so we continued and arrived at evening, not a moment too soon finding the place. It was, you may say, satisfactory.

All this was a long time ago. I remember, and I would do it again, but set down this, set down this. Were we led all that way for birth or death? There was a birth, certainly. We had evidence and no doubt. I had seen birth and death, but had thought they were different. This birth was hard and bitter agony for us, like death, our death.

We returned to our places, these kingdoms, but no longer at ease here, in the old dispensation, with an alien people clutching their gods. I should be glad of another death.

“A Song for Simeon.”

Lord, the Roman hyacinths are blooming in bowls and the winter sun creeps by the snow hills. The stubborn season has made stand. My life is light, waiting for the death’s wind like a feather on the back of my hand. Dust in sunlight and memory in corners wait for the wind that chills towards the dead land. Grant us Thy peace.

I have walked many years in this city, kept faith and fast. Provided for the poor. Have given and taken honor and ease. There went never any rejected from my door. Who shall remember my house? Where shall live my children’s children when the time of sorrow is come? They will take to the goat’s path and the fox’s is home flying from the foreign faces and the foreign swords.

Before the time of cords and scourges and lamentation, grant us Thy peace. Before the stations of the mountain of desolation, before the certain hour of maternal sorrow. Now at this birth season of decease, let the infant, the still unspeaking and unspoken word grant Israel’s consolation to one who has 80 years and no tomorrow. According to Thy word.

They shall praise Thee and suffer in every generation with glory and derision. Light upon light, mounting the saints’ stair. Not for me, the martyrdom, the ecstasy of thought and prayer. Not for me, the ultimate vision. Grant me Thy peace. And a sword shall pierce Thy heart, Thine also.

I am tired with my own life and the lives of those after me. I am dying in my own death and the deaths of those after me. Let Thy servant depart having seen Thy salvation.

“Difficulties of a Statesman.”

Cry? What shall I cry? All flesh is grass. Comprehending the companions of the bath, the Knights of the British Empire, the Cavaliers, oh, Cavaliers of the Legion of Honor. The Order of the Black Eagle, first then second class. And the Order of the Rising Sun.

Cry, cry, what shall I cry? The first thing to do is to form the committees, the consultative councils, the standing committees, select committees and subcommittees. One secretary will do for several committees. What shall I cry? Arthur Edward Cyril Parker is appointed telephone operator at the salary of 1 pound, 10 a week rising by annual increments of 5 shillings to 2 pounds, 10 a week. With a bonus of 30 shillings at Christmas and one week’s leave a year.

A committee has been appointed to nominate a commission of engineers to consider the water supply. A commission is appointed for public works, chiefly the question of rebuilding the fortifications. A commission is appointed to confer with the Volscian commission about perpetual peace. The fletchers and javelin-makers and smiths have appointed a joint committee to protest against the reduction of orders.

Meanwhile, the guards shake dice on the marches, and the frogs, O Mantuan, croak in the marshes. Fireflies flare against the faint sheet lightning. What shall I cry? Mother, mother, here is the row of family portraits, dingy busts, all looking remarkably Roman, remarkably like each other, lit up successively by the flare of a sweaty torchbearer yawning.

Oh, hidden under the, hidden under the, where the dove’s foot rested and locked for a moment, a still moment, repose of noon, set under the upper branches of noon’s widest tree. Under the breast feather stirred by the small wind after noon. There, the cyclamen spreads its wings. There, the clematis droops over the lintel.

Oh, mother, not among these busts all correctly inscribed. I, a tired head among these heads, necks strong to bear them, noses strong to break the wind. Mother, may we not be some time, almost now, together? If the mactations, immolations, oblations, impetrations are now observed, may we not be, oh hidden, hidden in the stillness of noon in the silent crooking night?

Come with the sweep of the little bat’s wing, with the small flare of the firefly or lightning bug. Rising and falling, crowned with dust. The small creatures, the small creatures chirp thinly through the dust through the night. Oh, mother, what shall I cry? We demand a committee, a representative committee, a committee of investigation. Resign! Resign! Resign!

Poetry of the past

Benjamin Larnell

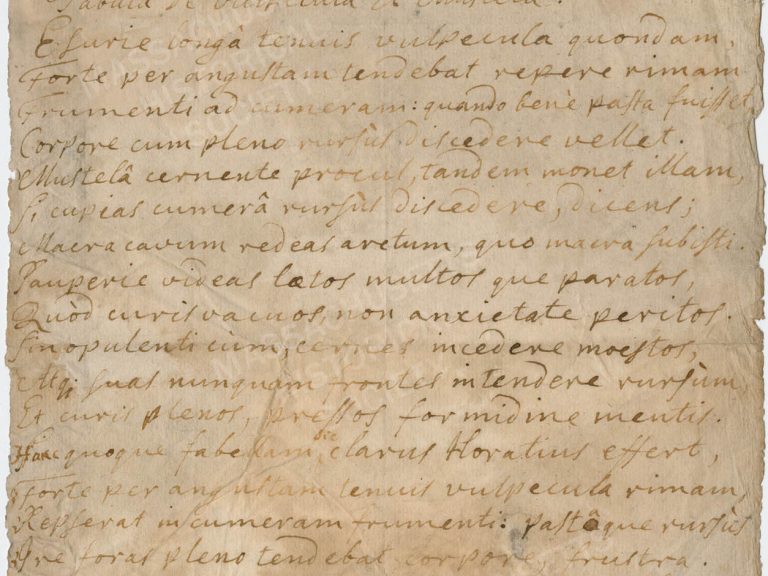

Nipmuc student Benjamin Larnell (ca. 1694–1714) was the last colonial-era Native American student to attend Harvard. Like all students of the day, Larnell was required to speak and write Latin prose and verse before admission. In this poem, which was possibly used to gain entrance to Harvard, Larnell turned a fable by Aesop into Latin verse.

Transcript and Translation

Original Latin Transcript

Fabula De Vulpeculâ Et Mustelâ

Esurie longâ tenuis vulpecula quondam,

Forte per angustam tendebat repere rimam

Frumenti ad cumeram: quando benè pasta fuisset

Corpore cum pleno rursùs discedere vellet.

Mustelâ cernente procul, tandem monet illam,

Si cupias cumerâ rursus discedere, dicens;

Macra cavum redeas arctum, quo macra subisti.

Pauperie videas laetos multosque paratos,

Quòd curis vacuos, non anxietate peritos.

Sin opulenti cùm, cernes incedere moestos,

Atque suas nunquam frontes intendere rursùm,

Et curis plenos, pressos formidine mentis.

Hanc quoque fabellam sic clarus Horatius effert,

Forte per angustam tenuis vulpecula rimam,

Repserat in cumeram frumenti: pastøque rursùs

Ire foras pleno tendebat corpore, frustra.

Cui mustela procul, si vis, ait effugere isthinc,

Macra cavum repetas arctum, quem macra subisti.

English Translation

Fable of the Fox and the Weasel

Once upon a time a fox, thin because of long-standing hunger,

happened to be striving to creep through a narrow crack

into a bin of grain. When he had eaten his fill,

he was eager to leave again with his stuffed belly.

A weasel, watching from afar, at last advised him,

saying, “You must return through the narrow hole as skinny as when you entered it.”

You could see many people happy in their poverty and well supplied,

because they are free from cares and know no anxiety,

but when they are wealthy, you will see them walk in sadness

and never unfurrow their brows

and be full of cares, weighed down by fear in their minds.

Famous Horace also tells this fable as follows:

“By chance a thin fox had crept into a bin of grain

through a thin crack; having eaten he

kept trying to go outside again with his full belly to no avail.”

Credits

Poem written by Benjamin Larnell, ca. 1711–1714

Translation by Thomas Keeline and Stuart M. McManus

Read by Richard Tarrant

Audio courtesy of The Peabody Museum

Image courtesy of Massachusetts Historical Society

Poetry in the present

Speak, memory

Alaskan poet and Radcliffe fellow Joan Naviyuk Kane shares her dedication to sustaining King Island Inupiaq, her Native Alaskan language, through poetry.

Poetry for the future generations

A public classroom

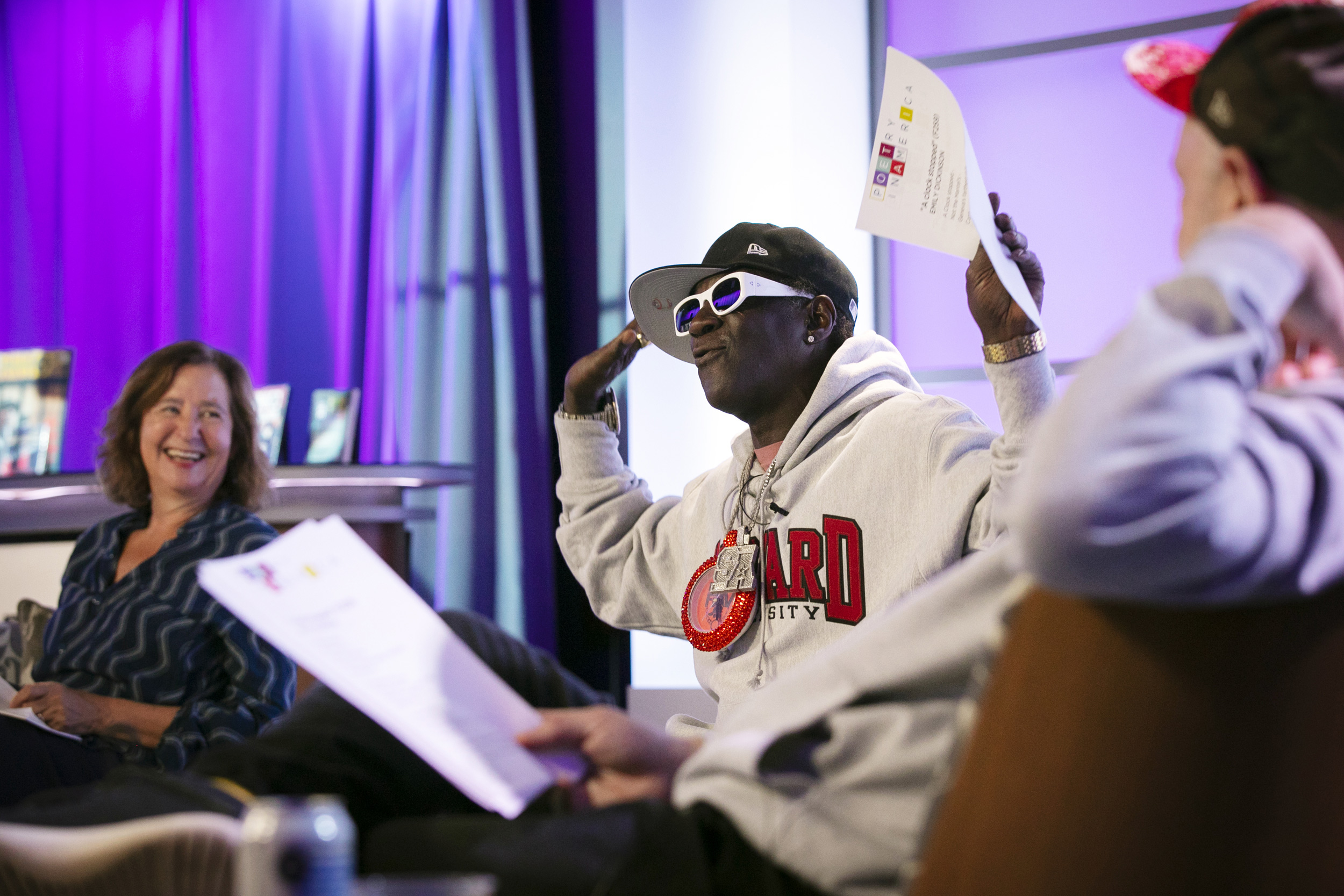

Created and directed by Harvard professor Elisa New in partnership with Harvard, “Poetry in America” is a public television series and multi-platform educational initiative that brings poetry into classrooms and living rooms around the world.

“Poetry in America” offers free online courses for global learners as well as for-credit and professional development courses for undergraduates, graduate students, highly motivated high-school students, and educational practitioners.

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE