Environmental Exposure

Environmental Exposure

The ideas, research, and actions from across Harvard University aimed at finding solutions to climate change, pollution, and environmental contamination for all communities.

In pursuit of climate justice

Two Harvard groups are working to right the wrongs of decades of discriminatory environmental policies with the hope of reversing their effects on the next generation.

Winds of change

Members of the Harvard community are taking a variety of approaches to finding solutions to environmental and health inequalities.

From the experts

“Pandemics like COVID reveal in the most painful way what we need to fix in the world.”

Since the outset of the COVID-19 outbreak, public health experts have noted the disproportionate toll on Black and brown Americans. Those groups are at much greater risk of getting infected than white people; they are two to three times likelier to be hospitalized, and twice as likely to die, according to recent estimates from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control.

Podcast

The turning point

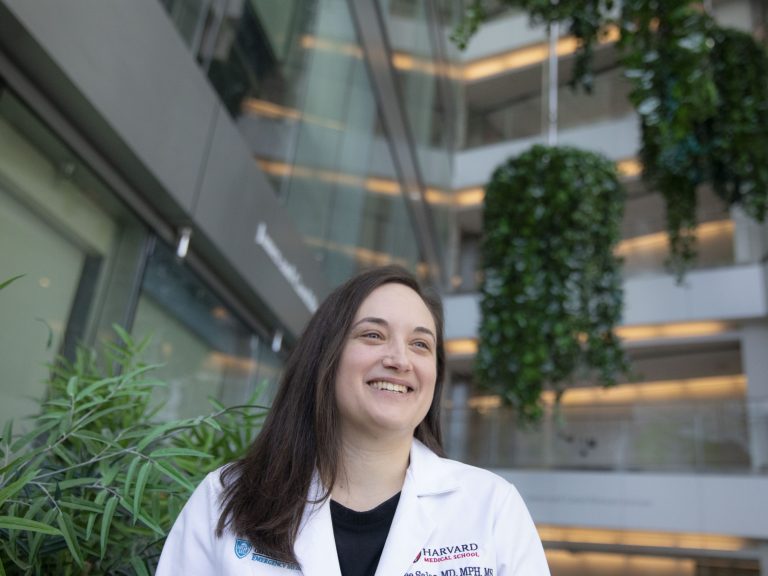

Emergency room doctor and C-CHANGE Yerby Fellow Renee Salas discusses how climate change is impacting the everyday health of African American, Latinx, and Indigenous Americans, and why she is hopeful that America is at a turning point.

Transcript

Over the past year, the phrase “systemic racism” has gained popularity across the United States. But what does it mean, and how does it affect people? To help us understand the phrase and shed light on it in context, we spoke with Dr. Renee Salas, an emergency room doctor and a Yerby Fellow at the Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment at the Harvard University T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

If systemic racism is the umbrella term, then “environmental racism” can be viewed as one offshoot of that system. Dr. Salas and her colleagues at the Lancet Countdown have done tremendous research on environmental racism, and how it now intersects with climate change. She lays out not only their research and what studies have shown, but also gives detailed examples of environmental racism from just this past year in the United States.

And as you’ll hear her describe, environmental racism has long been a problem, and now coupled with climate change, it is producing massive negative outcomes for those who are experiencing it firsthand, affecting their overall health, wellbeing and more.

I’m Rachel Traughber, and I’m Jason Newton. And this in Unequal: a Harvard University series exploring race and inequality in the United States.

Rachel Traughber (RT): Thank you for joining us today. Dr. Salas, what is environmental racism?

Dr. Renee Salas: Great question. So environmental racism is essentially racial discrimination in policymaking and determining how to enforce regulations and laws that lead to polluting industry and health harming poisons in pollutants being placed in and around communities of color, so thus targeting communities of color. But even beyond that, it also excludes these communities from the very process itself. So, whether that’s decision-making boards or commissions or regulatory bodies. And in my mind, it really gets to the root, as we need to ask these really important questions of why are things the way they are, and recognize how are decisions being made that determine where we put this polluting infrastructure, and who is being most exposed.

RT: So, I know that you’re the lead author of The Lancet 2020 report, which looks at health and equity and health and climate change broadly in the United States. And in the context of that report, you and your colleagues across the US did a case study that specifically looked at the effect of environmental racism in Louisiana with Hurricane Laura, I’m wondering if you could share a little bit about what you found.

RS: Yeah, we really felt Hurricane Laura provided a key example for us to tie environmental racism to health, because again, we’re a group of health professionals from across the U.S. that work at this nexus. So, I think it’s important though, just to paint a picture about what happened with Hurricane Laura when it struck Louisiana on August 27, 2020.

So first off, recognize that this was still early in the COVID-19 pandemic, so well before vaccines. So, there were heavy winds and storm surges and extensive inland flooding, and this caused extensive damage to infrastructure, but also caused widespread power outages, and contaminated water, so there wasn’t even clean water available. But this didn’t happen just right after the event, it was still present even three weeks later. People were still without electricity and having to boil their water. In fact, people were trying to use generators but dying of carbon monoxide poisoning as they tried to find workarounds. And local hospitals were actually forced to evacuate or severely limit the services they could provide just because they didn’t have electricity or water, so leaving people without options for healthcare.

Now, this is bad. But then on top of that, there was a heat wave and actually the heat index rose to 110 degrees Fahrenheit, and that’s sort of how hot it feels with humidity. But there was still no electricity to use air conditioning! So, for people though, who actually live in the Lake Charles area, in the Calcasieu Parish, there was still even more issues and that was because a bio lab chemical plant actually caught fire due to damage from the hurricane, and this led to residents now also being exposed to toxic gases and pollutants. So, it got to the point where they actually were told to stay home and close their doors, their windows and not to use their air conditioning units if they even had power to try to use them.

So, you know, I just really sit with that for a moment and realize what an impossible situation this is, you have a damaged home, you have no electricity, keep yourself cool, no clean water. If you try to go to a cooling shelter, even if they exist, you run the risk of contracting COVID-19. But now there’s toxic fumes to which you’re not even supposed to step outside and breathe the air. We actually don’t even know how bad the exposure really was because regional monitors were offline after the storm.

So, as we go back to that question of environmental racism of why, why did this happen, and why were things the way they were? This directly ties health to environmental racism, because environmental racism is why there are so much toxic pollutants, and oil and gas and other chemical infrastructure in that area. So, these people, in the Calcasieu Parish, have been chronically exposed well before this hurricane [to] some of the highest levels of toxic industrial emissions in the country, as hundreds of oil, gas and chemical facilities are there and even dozens more had been improved. Sorry, approved, recently, and at some of the worst in the US for environmental justice indicators, which really tries to capture inequities and injustices.

Now, I mean, that alone has significant implications for health, because people there have higher rates of cancer and asthma, other lung diseases, depression and different poor pregnancy outcomes. So, the reality is that these people are bearing the biggest brunt and bore the biggest brunt and most dangerous brunt for health after the storm. And climate change is only going to intensify extreme weather and make these situations much more frequent, and really highlights the urgency with which we need action.

RT: Clearly, there’s a big problem. The story you’ve related today is really, really powerful, and kind of terrifying to think about it happening in the United States, one of the wealthiest countries on the planet. And it’s also very obviously affecting some groups of people more than others. Knowing those two things, that this is a really massive problem, and it’s going to take hands from all sides to get things done, how do you approach even beginning to dig in on something like this, either from a policy perspective or from, you know, a neighborhood perspective? What does that look like?

RS: I mean, I view when I tell residents this in the emergency department, as far as you know, you, when you think about a diagnosis for a patient, or what could be going on when a patient presents, you have to think about it in order to even come to that diagnosis. So if somebody presents with chest pain, if you don’t think that it could be a heart attack, then you’re never going to find or diagnose the heart attack. And I think that that really resonates here, because we have to see the problem for what it is and understand why things are the way they are in order for us to fix them and diagnose them and then develop problems. And I think that we’ve been in this really profound moment as a country, where we are reflecting on the inequities and disparities from structural racism in a profoundly more pronounced way than at least I’ve ever experienced in my lifetime. And I’m hoping that this can just exponentially increase and especially for us in the health community, to tackle these health disparities, and recognize that they’re intertwined and interconnected with climate solutions. So, we cannot address these health disparities from racism without also addressing climate change, because these populations are also disproportionately bearing the health harms from climate change.

So, we need to talk about it more, make these interconnections, or interconnected relationships, clear for people just so they can connect the dots. I mean, I feel like that’s a lot of what we’re doing. And then we need these interconnected solutions and to recognize that it can be overwhelming to try to tackle them all at once. But this is what we have to do, and it actually will allow us to address multiple issues.

And we need to their voices at the table. So, these communities that are being most impacted, we need to make sure that their voices are heard and that they are at the table where decisions are being made and they can help us craft solutions that they know will work for them. And that’s something we’re really looking at the next evolution of our work is to have them be involved at the very beginning.

RT: One of the things that I found particularly compelling about your approach through the Lancet is that you do look at this as an interdisciplinary problem, that it’s not just a science issue. It’s not just a climate issue. It’s not just a social issue, but it’s a sort of toxic brew, if you will, of all three things. What gives you hope for the future, when you when you see this group of people that are that are showing up to do some of this work? What are what is what does that look like?

RS: Yeah, I, there are enormous reasons for hope. And I am the most hopeful that I have been, during my work on climate change now, which I recognize may be surprising given the year that we have all lived through. But it’s because people are…are…the proverbial rose-colored glasses are knocked off. And people are seen that on this accelerated timeline, what has happened with the COVID-19 pandemic, when we fail to respond to the science and act equitably and have a foundation that is an optimal going into this, for the pandemic, that we don’t want the same mistakes to happen with climate change.

So just like, you know, I have a patient that comes into my emergency department, and I consult different services to make sure we get their optimal care. It is the same thing with this work, as you outlined in the sense that we need multiple disciplines to come to the table and everyone to lend their respective expertise and perspective, so that we can build robust interdisciplinary solutions. And it’s happening! Silos are getting broken down. I know in academics; we love our siloed departments. But I think people are realizing that that is not going to tackle these complex issues. And that’s what gets me out of bed every morning is to work with amazing groups of individuals who are passionate about improving health and creating a world that is more equitable and healthy for everyone. And we can do it, I’m convinced that we can come together and make the changes that are needed.

RT: Conversely, I wonder if you might share what you think is the absolute most concerning, I mean, you know, obviously, we’re at a point in human history where climate change is at the front of many people’s minds. I’m wondering, in terms of where it intersects with health, what are, what are those small, but really important items that need to happen, so that we save lives?

RS: You’re right, in… Another analogy from my emergency medicine practice is that when a patient’s crashing in front of me, oftentimes I have a small critical window to give a treatment. And so if I don’t give it in that critical window, and I give it too late, it may not work or work as well. And the reality is that we have to cut our global carbon emissions in half by 2030 — only nine years from now. And to net zero by 2050, if we want to try to keep average global warming to below 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2100.

So we are in a historic moment in that critical window where we have to act now. And if we act too late, it will not have the same impact, or again may not work nearly as well or at all. And when I think about if we don’t do that and get to above 1.5 degrees Celsius, and even beyond, because we’re on track now to with current commitments to be upwards of four degrees Celsius, you know, that’s just catastrophic for health. So, fundamentally, we have to also address mitigation and get to this root cause.

But there are so many areas where we can begin to protect patients and adapt and make our systems more resilient. So, you know, for example, things like making sure our public health departments are funded and able to identify and optimally protect in an evidence-based way those who are most critical, whether we’re thinking about heat, or extreme weather or other climate exposures. And that’s just one example of many. But we can begin to implement that now.

RT: Where should people go to learn more about your work?

RS: Well, I have to continue to boast about the Lancet Countdown, and not because of me! I often say I feel like I just put the initial brushstrokes on the paper, and it’s the working group that really forms it into its final picture. So, I would encourage you to go see the work of the whole landscape countdown Working Group, which is over 70 institutions, organizations and centers. So that’s at www.LancetCountdownUS.org. And you can see our past briefs, which we also hope every year builds on the last, and are still relevant.

And I would also say if you really want to, if you love to click around on web pages, then there is an interactive perspective, actually at the New England Journal of Medicine under their climate crisis and health page, which you might think okay, this seems like it’s just for doctors, but we really tried to make it fully accessible to everyone where you can click around and see how different health problems can connect back to greenhouse gases, and hopefully try to help make some of these connections on how everything works together and sort of the upstream causes.

RT: Great, thank you so much for joining us today. We really appreciate it.

RS: Thank you. It was an honor and privilege to be here. Thank you.

From the experts

Radiation illnesses and COVID-19 in the Navajo Nation

COVID-19 is killing Native Americans at nearly three times the rate of whites, and on the Navajo Nation itself, about 30,000 people have tested positive for the coronavirus and roughly 1,000 have died. But among the Navajo (or Diné), the coronavirus is also spreading through a population that decades of unsafe uranium mining and contaminated groundwater has left sick and vulnerable.

Where we’re focused

These are just a few of the initiatives Harvard Schools have created to take on these important issues.

Learn more

A collection of podcasts that explore ideas around environment, health, race, and inequality.

Covid state of play: Covid, racism, and environmental justice

Erin Brockovich and Caitlin McCoy on water pollution regulations and effective advocacy

Energy, climate policy, and social justice: A conversation with Vicky Bailey

Free online courses

Join the effort to fight environmental and structural racism.

Explore the series

Unequal

“Unequal” is a multi-part series highlighting the work of Harvard faculty, staff, students, alumni, and researchers on issues of race and inequality across the United States.

Unequal- Democratic Deficits

Making democratic institutions and elections more representative.

- Let all the voices be heard

Aaron Mukerjee talks about the Voting Rights Litigation Clinic.

- Criminal Injustice

Creating a more equitable criminal justice system.

The ideas, research, and actions from across Harvard University for creating a more equitable criminal justice system.

- An overhaul for justice

Ana Billingsley talks about strategies to effect real change in the criminal justice system.