Unequal

A series on race and inequality across the United States.

In FocusPart 1

Criminal Injustice

The ideas, research, and actions from across Harvard University

for creating a more equitable criminal justice system.

Solving racial disparities in policing

Experts say that the approach must be comprehensive because the roots of injustice are embedded in our culture.

The right to remain vocal

Members of the Harvard community on the many approaches needed to have a truly just criminal justice system.

Personal essay

“There’s no system too big to reimagine—not even the criminal justice system.”

Ana Billingsley, assistant director with the Government Performance Lab at the Harvard Kennedy School, on translating an appetite for change into reality.

Podcast

The flaws in our data

Harvard professor and computer scientist Latanya Sweeney discusses issues surrounding the increased use of data and algorithms in policing and sentencing.

Transcript

JASON NEWTON Data, and the algorithms that interpret data, are everywhere. From predicting which advertisements to send to your social media feeds, to using your location data to track which stores you frequent, society constantly leverages data to make decisions – even in the criminal justice system. Data and algorithms are being used in policing to predict where crimes might take place, and during sentencing to predict whether or not someone convicted of a crime is likely to reoffend.

But with the long history of systemic racism within the United States criminal justice system, does that mean the algorithm itself will be flawed by racist and prejudicial assumptions?

JN I’m Jason Newton…

RACHEL TRAUGHBER …and I’m Rachel Traughber, and this is Unequal: a Harvard University series exploring race and inequality across the United States.

RT To answer this question and shed light on how our data and algorithms are being used more broadly, we’re joined today by computer scientist Latanya Sweeney, Professor of the Practice of Government and Technology at the Harvard Kennedy School and in the Harvard Faculty of Arts and Sciences. She is an expert on data privacy, director of the data privacy laboratory at Harvard, and is widely regarded as one of the most preeminent voices in the field. She joins us now with more.

JN Professor Sweeney, give us a brief description of what these data algorithms are, what they tell us and how is it they are now used in our criminal justice system.

LATANYA SWEENEY Sure, thank you. Society has definitely experienced exponential growth in the amount of information collected on individuals. The idea now is not only do you have the collected data, but how do we use that data to make decisions. And that’s where these data algorithms come in. They analyze the data, they look for models, they make predictions, and they can be used to help humans make decisions.

One of the places they can do that is in the criminal justice system. There are all types of decisions that are made there and lots of historical data on which an algorithm can learn. One of those examples is recidivism: This is the place where you try to decide whether or not a person will be allowed to go out on bail. So just because someone’s arrested doesn’t mean they’re guilty, that’s where the trial to decide. But whether or not they’ll be allowed to go out on bail is a decision that has to be made, usually by a judge, and a recidivism algorithm can use historical data to make that recommendation.

JN Okay, but could you tell us what some of the drawbacks are to using this technology, as it tries to predict human behavior?

LS Definitely, there are two major areas in which these drawbacks can happen. One is the date on which the algorithm has to learn or it’s going to learn these models to make its predictions, and the other one is when the algorithm uses a feedback from the person who is giving the information. And they say, Yes, I like that it gives me more like that, or give me less like that. So the bias in the algorithm example, is in the recidivism algorithm that I talked about, if judges before had been making biased decisions about who was allowed to go out on bail and who wasn’t, the algorithm will pick up that bias, and will then continue to perpetuate those decisions. If the algorithm has a feedback system, and it makes a recommendation, and a judge doesn’t like it says, I don’t really agree with that one, then over time, the algorithm will adjust to the preferences or biases that the judge may have.

The example I think that most people really understand is when people are being recommended for a job. So there are many algorithms now that will take a bank of resumes and when there’s a job opening, or recommend people based on their resume to the potential employer. The potential employer then says yes, this one comes for an interview, not those. But if that employer has a bias against older people, then in fact, only young people will come be offered to offered to that person for interview. And on the next time that employee use it, it will only recommend younger people. So now the bias is even trapped in even further.

RT I would like to unpack a little bit about these data algorithms applied to search results. I know that you’ve done some particular research on this and had some interesting discoveries. And I wonder if you would share a little bit about that with us?

LS: In fact, that’s what started this area of research on algorithmic fairness, I had just become a professor here at Harvard. And I was in my office, when I was being interviewed by a reporter. I wanted to show him a particular paper. So I typed My name into the search bar onto the Google search bar, and up pop the paper I was looking for, but also a popped an ad implying I had an arrest record. And so the reporter said, I forget that paper, tell me about when you’re arrested. And I said, Well, I haven’t been arrested. But eventually I had to click on the link, pay the money, and show him that not only did it not have an arrest record for me, but with my unusual name, there was no one else who had an arrest record with that name, either.

But that started me on the question of why did that happen. And so I spent hours and then a couple of months, and what I came to learn was that those ads came up, implying you had an arrest record, if you search the name of a real person, their first and last name, and if their first name was given more often to a black baby than a white baby, and they were 80% likely to have an arrest record show up. And and the opposite. If the baby the first name was given more often to white babies.

Discrimination in the United States is not illegal. But [for] certain people in certain situations, discrimination is illegal. One of those…one of those groups of people are Blacks, and one of those situations is employment. And so if two people were applying for a job, and a search implies that one of them has an arrest record and the other one doesn’t, they’re put at a disadvantage. So this was the first time an algorithm, in this case, Google Search, was found to be in violation of the Civil Rights Act.

JN That’s a really good point. So from the bias in the in the courtroom to out in the community, brings me to my next question, how have aggressive police tactics, and the over policing of black and minority neighborhoods over the past several decades affected this type of algorithm?

LS Right, this is a fantastic question. We don’t we can’t even say we know the exact answer because we have to be able to say “this is exactly its impact on the data.” As we look at studies who show its impact on the data, then the question is, can we account for that when the algorithms are learning? So if the data is biased, the result from the algorithm is going to be biased?

I’ll give you a Harvard example. Many years ago, when I was at Harvard, you know, pretty much it was primarily young white men, or certainly we can imagine a time even earlier than that, where was young white men. If we wanted to make an admissions algorithm for Harvard at that time, we would have used the admissions data that had that had been used. The algorithm would learn things and the population that we would get would be young white guys. So the data we provide to the algorithm has a lot to determine about what the algorithm will put out. Often I speak to students, and it really brings that home to them. Harvard’s campus right now is so diverse. When you look at in the classroom, it’s just an amazing, these are the best minds in the world. And they come from all different walks of life, all different countries. When they say wait a second, this room would look – look how different it would look, and not based on the same criteria.

RT We’ve spoken a lot about how these algorithms can be used nefariously or unwisely, I’m wondering if you can suggest some opportunities that they could be adjusted for good and what that future might look like.

LS Well, I’m a computer scientist, I want society to enjoy the benefits of these new technologies! I want society to enjoy the benefits, but without sacrificing these important historical protections. There’s no reason that that can’t be done. In every example that I’ve talked about today, we can imagine and envision ways two different things that can be done. One is an analysis of the data and the algorithm that can provide a guarantee of what it won’t do, of what kind of bias it doesn’t exhibit. The second kind of thing we can imagine is actually changing the algorithm so that it itself does it offsets a racial bias result. So the advertising algorithm would be an example of that.

RT And last, I just wonder if you might give us any insight into you know, what kind of oversight goes into algorithms in general? I mean, it sounds like based on the conversation we’ve had here today that people are sort of, this is new technology, people are just applying it as they see fit, because they think it might make their jobs easier, or their lives easier. And instead, it’s…it’s exacerbating some of the inequalities that we’re seeing. Is there any oversight of these from a governmental perspective from a nonprofit perspective? Like, how, what is the next step in terms of policy creation?

LS Yeah, this is a fantastic question. You know, it’s part of a larger arc. It’s not just these algorithms, it’s technology design, and designers are the new policymakers. We don’t elect them, we don’t vote for them, but the arbitrary decisions they make, and the technology products they produce dictate how we live our lives. And that’s everything from free speech, to…to privacy, to things like these decision-making algorithms that we’ve been talking about today. And so there’s a bigger arc around, how do we address technology itself and its impact on society. Our historical protections are intact, but they don’t seem to know how to apply or adapt themselves to the current technology.

So one big answer we need is a new kind of technologist, one who works in the public interest, working in all of these places, and [with] all these stakeholders, working in technology design and technology companies working in agencies that regulate for these rules, so that they can understand them, working in Congress, and so forth.

RT Yeah, I think we’ve definitely seen what happens when we don’t have people doing that work. But the you know, the events of January 6, in particular, and how a lot of that liaising to make that experience happen happened online happened through technology not being regulated. So it would be interesting to see what the next step would be to prevent something like that, and how technology could be used productively and positively to help.

LS Yeah, and I would just say, you know, Twitter provides a great example, as well. Twitter has its own definition of free speech. And it’s a private company, so it can have this other definition of free speech. But Americans want to talk about Americans definition, America’s definition of free speech, and somehow be upset if Twitter doesn’t quite satisfy it. And and the other thing I’ve heard is Americans interpreting Twitter’s version as if it is America’s version. It just shows you how pervasive the technology is, and how the design of Twitter as an example, is really dictating what we think our free speech rights are.

RT If you liked what you heard today and are anxious to learn more from Harvard’s Unequal project, visit us online at the “in focus” section of harvard.edu.

Video

A history that can’t be suppressed

Bryan Stevenson discusses the legacy of slavery and the vision behind creating the National Memorial for Peace and Justice and The Legacy Museum in Montgomery Alabama.

Profile

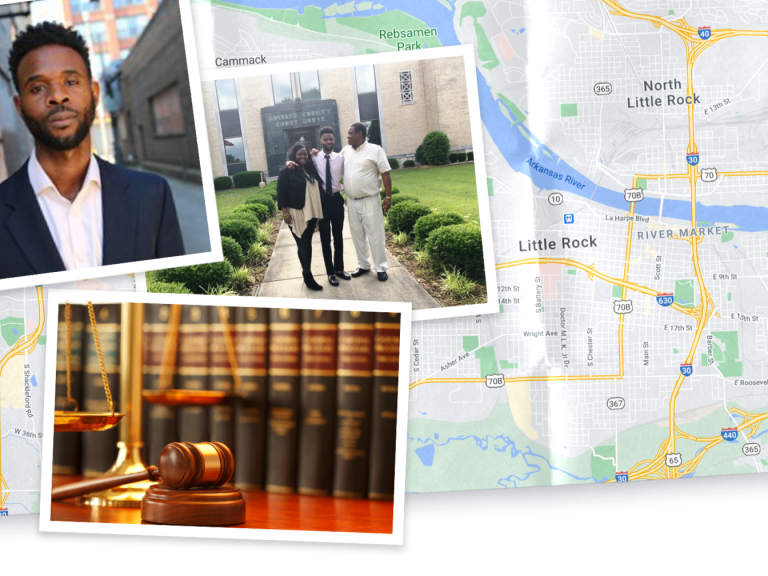

Undoing injustice

Omavi Shukur went into law because he felt it was “the most effective route to go on that [would] allow me to help change people’s material reality for the better.”

Where we’re focused

These are just a few of the initiatives Harvard Schools have created to take on these important issues.

Learn more

“Policing in America” is a Harvard Law School lecture series on American policing in the current moment, what brought us here, and opportunities for improvement.

In FocusPart 2

Democratic Deficits

The ideas, research, and actions from across Harvard University aimed at making democracy, democratic institutions, and elections more representative

Fighting for equality at the ballot box

“I want to tell every disillusioned person who is waffling on whether to participate in the process for the first time or wondering whether to keep participating in a process that feels like it’s stacked against them, we’re on the watch.”

— Sarah Gonski, Harvard Law School alum and voting rights advocate

Raising voices

Members of the Harvard community are taking a variety of approaches to finding solutions to our imperfect election system.

Essay

“… fulfilling America’s promise requires building a democracy that includes all of us.”

Aaron Mukerjee, a third-year student at Harvard Law School, talks about his work with the Voting Rights Litigation Clinic.

Podcast

Fixing the vote

In his book, Professor Alex Keyssar explores why we still have an electoral college in America and discovers a complex mix of politics, constitutional law, structural racism, and more.

Video

On account of race

A roundtable conversation, featuring scholars who have pioneered innovative approaches to the past, present, and future of political empowerment, looks at the relationships among the Reconstruction Amendments, the 19th Amendment, the VRA, and the INA.

Profile

The roots of the reckoning

Lawrence D. Bobo, dean of social science and the W.E.B. Du Bois Professor of the Social Sciences, talks about confronting the long shadow cast by America’s history of deeply fraught race relations and entrenched inequality.

Where we’re focused

These are just a few of the initiatives Harvard Schools have created to take on these important issues.

Learn more

Selma Online

A visual history of The Civil Rights Movement leading to The Voting Rights Act of 1965.

A reading list on issues of race

Harvard faculty recommend the writers and subjects that promote context and understanding.

In FocusPart 3

Environmental Exposure

The ideas, research, and actions from across Harvard University aimed at finding solutions to climate change, pollution, and environmental contamination for all communities.

In pursuit of climate justice

Two Harvard groups are working to right the wrongs of decades of discriminatory environmental policies with the hope of reversing their effects on the next generation.

Winds of change

Members of the Harvard community are taking a variety of approaches to finding solutions to environmental and health inequalities.

From the experts

“Pandemics like COVID reveal in the most painful way what we need to fix in the world.”

Since the outset of the COVID-19 outbreak, public health experts have noted the disproportionate toll on Black and brown Americans. Those groups are at much greater risk of getting infected than white people; they are two to three times likelier to be hospitalized, and twice as likely to die, according to recent estimates from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control.

Podcast

The turning point

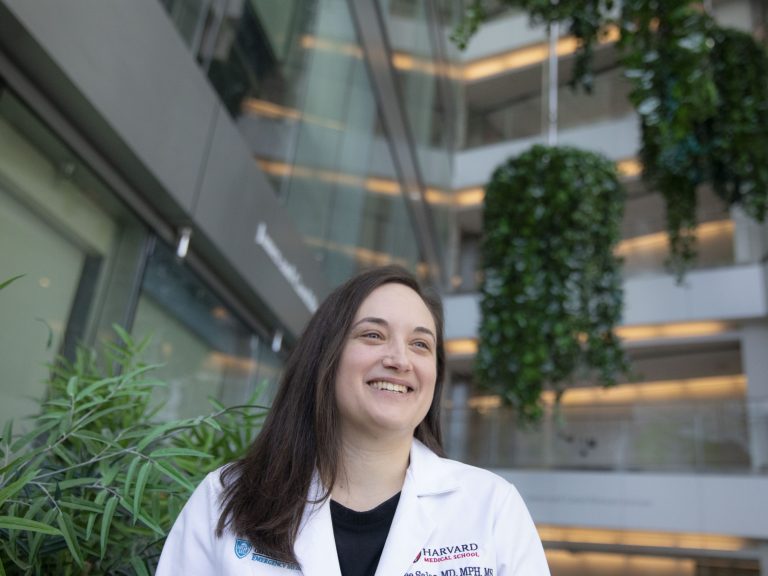

Emergency room doctor and C-CHANGE Yerby Fellow Renee Salas discusses how climate change is impacting the everyday health of African American, Latinx, and Indigenous Americans, and why she is hopeful that America is at a turning point.

Transcript

Over the past year, the phrase “systemic racism” has gained popularity across the United States. But what does it mean, and how does it affect people? To help us understand the phrase and shed light on it in context, we spoke with Dr. Renee Salas, an emergency room doctor and a Yerby Fellow at the Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment at the Harvard University T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

If systemic racism is the umbrella term, then “environmental racism” can be viewed as one offshoot of that system. Dr. Salas and her colleagues at the Lancet Countdown have done tremendous research on environmental racism, and how it now intersects with climate change. She lays out not only their research and what studies have shown, but also gives detailed examples of environmental racism from just this past year in the United States.

And as you’ll hear her describe, environmental racism has long been a problem, and now coupled with climate change, it is producing massive negative outcomes for those who are experiencing it firsthand, affecting their overall health, wellbeing and more.

I’m Rachel Traughber, and I’m Jason Newton. And this in Unequal: a Harvard University series exploring race and inequality in the United States.

Rachel Traughber (RT): Thank you for joining us today. Dr. Salas, what is environmental racism?

Dr. Renee Salas: Great question. So environmental racism is essentially racial discrimination in policymaking and determining how to enforce regulations and laws that lead to polluting industry and health harming poisons in pollutants being placed in and around communities of color, so thus targeting communities of color. But even beyond that, it also excludes these communities from the very process itself. So, whether that’s decision-making boards or commissions or regulatory bodies. And in my mind, it really gets to the root, as we need to ask these really important questions of why are things the way they are, and recognize how are decisions being made that determine where we put this polluting infrastructure, and who is being most exposed.

RT: So, I know that you’re the lead author of The Lancet 2020 report, which looks at health and equity and health and climate change broadly in the United States. And in the context of that report, you and your colleagues across the US did a case study that specifically looked at the effect of environmental racism in Louisiana with Hurricane Laura, I’m wondering if you could share a little bit about what you found.

RS: Yeah, we really felt Hurricane Laura provided a key example for us to tie environmental racism to health, because again, we’re a group of health professionals from across the U.S. that work at this nexus. So, I think it’s important though, just to paint a picture about what happened with Hurricane Laura when it struck Louisiana on August 27, 2020.

So first off, recognize that this was still early in the COVID-19 pandemic, so well before vaccines. So, there were heavy winds and storm surges and extensive inland flooding, and this caused extensive damage to infrastructure, but also caused widespread power outages, and contaminated water, so there wasn’t even clean water available. But this didn’t happen just right after the event, it was still present even three weeks later. People were still without electricity and having to boil their water. In fact, people were trying to use generators but dying of carbon monoxide poisoning as they tried to find workarounds. And local hospitals were actually forced to evacuate or severely limit the services they could provide just because they didn’t have electricity or water, so leaving people without options for healthcare.

Now, this is bad. But then on top of that, there was a heat wave and actually the heat index rose to 110 degrees Fahrenheit, and that’s sort of how hot it feels with humidity. But there was still no electricity to use air conditioning! So, for people though, who actually live in the Lake Charles area, in the Calcasieu Parish, there was still even more issues and that was because a bio lab chemical plant actually caught fire due to damage from the hurricane, and this led to residents now also being exposed to toxic gases and pollutants. So, it got to the point where they actually were told to stay home and close their doors, their windows and not to use their air conditioning units if they even had power to try to use them.

So, you know, I just really sit with that for a moment and realize what an impossible situation this is, you have a damaged home, you have no electricity, keep yourself cool, no clean water. If you try to go to a cooling shelter, even if they exist, you run the risk of contracting COVID-19. But now there’s toxic fumes to which you’re not even supposed to step outside and breathe the air. We actually don’t even know how bad the exposure really was because regional monitors were offline after the storm.

So, as we go back to that question of environmental racism of why, why did this happen, and why were things the way they were? This directly ties health to environmental racism, because environmental racism is why there are so much toxic pollutants, and oil and gas and other chemical infrastructure in that area. So, these people, in the Calcasieu Parish, have been chronically exposed well before this hurricane [to] some of the highest levels of toxic industrial emissions in the country, as hundreds of oil, gas and chemical facilities are there and even dozens more had been improved. Sorry, approved, recently, and at some of the worst in the US for environmental justice indicators, which really tries to capture inequities and injustices.

Now, I mean, that alone has significant implications for health, because people there have higher rates of cancer and asthma, other lung diseases, depression and different poor pregnancy outcomes. So, the reality is that these people are bearing the biggest brunt and bore the biggest brunt and most dangerous brunt for health after the storm. And climate change is only going to intensify extreme weather and make these situations much more frequent, and really highlights the urgency with which we need action.

RT: Clearly, there’s a big problem. The story you’ve related today is really, really powerful, and kind of terrifying to think about it happening in the United States, one of the wealthiest countries on the planet. And it’s also very obviously affecting some groups of people more than others. Knowing those two things, that this is a really massive problem, and it’s going to take hands from all sides to get things done, how do you approach even beginning to dig in on something like this, either from a policy perspective or from, you know, a neighborhood perspective? What does that look like?

RS: I mean, I view when I tell residents this in the emergency department, as far as you know, you, when you think about a diagnosis for a patient, or what could be going on when a patient presents, you have to think about it in order to even come to that diagnosis. So if somebody presents with chest pain, if you don’t think that it could be a heart attack, then you’re never going to find or diagnose the heart attack. And I think that that really resonates here, because we have to see the problem for what it is and understand why things are the way they are in order for us to fix them and diagnose them and then develop problems. And I think that we’ve been in this really profound moment as a country, where we are reflecting on the inequities and disparities from structural racism in a profoundly more pronounced way than at least I’ve ever experienced in my lifetime. And I’m hoping that this can just exponentially increase and especially for us in the health community, to tackle these health disparities, and recognize that they’re intertwined and interconnected with climate solutions. So, we cannot address these health disparities from racism without also addressing climate change, because these populations are also disproportionately bearing the health harms from climate change.

So, we need to talk about it more, make these interconnections, or interconnected relationships, clear for people just so they can connect the dots. I mean, I feel like that’s a lot of what we’re doing. And then we need these interconnected solutions and to recognize that it can be overwhelming to try to tackle them all at once. But this is what we have to do, and it actually will allow us to address multiple issues.

And we need to their voices at the table. So, these communities that are being most impacted, we need to make sure that their voices are heard and that they are at the table where decisions are being made and they can help us craft solutions that they know will work for them. And that’s something we’re really looking at the next evolution of our work is to have them be involved at the very beginning.

RT: One of the things that I found particularly compelling about your approach through the Lancet is that you do look at this as an interdisciplinary problem, that it’s not just a science issue. It’s not just a climate issue. It’s not just a social issue, but it’s a sort of toxic brew, if you will, of all three things. What gives you hope for the future, when you when you see this group of people that are that are showing up to do some of this work? What are what is what does that look like?

RS: Yeah, I, there are enormous reasons for hope. And I am the most hopeful that I have been, during my work on climate change now, which I recognize may be surprising given the year that we have all lived through. But it’s because people are…are…the proverbial rose-colored glasses are knocked off. And people are seen that on this accelerated timeline, what has happened with the COVID-19 pandemic, when we fail to respond to the science and act equitably and have a foundation that is an optimal going into this, for the pandemic, that we don’t want the same mistakes to happen with climate change.

So just like, you know, I have a patient that comes into my emergency department, and I consult different services to make sure we get their optimal care. It is the same thing with this work, as you outlined in the sense that we need multiple disciplines to come to the table and everyone to lend their respective expertise and perspective, so that we can build robust interdisciplinary solutions. And it’s happening! Silos are getting broken down. I know in academics; we love our siloed departments. But I think people are realizing that that is not going to tackle these complex issues. And that’s what gets me out of bed every morning is to work with amazing groups of individuals who are passionate about improving health and creating a world that is more equitable and healthy for everyone. And we can do it, I’m convinced that we can come together and make the changes that are needed.

RT: Conversely, I wonder if you might share what you think is the absolute most concerning, I mean, you know, obviously, we’re at a point in human history where climate change is at the front of many people’s minds. I’m wondering, in terms of where it intersects with health, what are, what are those small, but really important items that need to happen, so that we save lives?

RS: You’re right, in… Another analogy from my emergency medicine practice is that when a patient’s crashing in front of me, oftentimes I have a small critical window to give a treatment. And so if I don’t give it in that critical window, and I give it too late, it may not work or work as well. And the reality is that we have to cut our global carbon emissions in half by 2030 — only nine years from now. And to net zero by 2050, if we want to try to keep average global warming to below 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2100.

So we are in a historic moment in that critical window where we have to act now. And if we act too late, it will not have the same impact, or again may not work nearly as well or at all. And when I think about if we don’t do that and get to above 1.5 degrees Celsius, and even beyond, because we’re on track now to with current commitments to be upwards of four degrees Celsius, you know, that’s just catastrophic for health. So, fundamentally, we have to also address mitigation and get to this root cause.

But there are so many areas where we can begin to protect patients and adapt and make our systems more resilient. So, you know, for example, things like making sure our public health departments are funded and able to identify and optimally protect in an evidence-based way those who are most critical, whether we’re thinking about heat, or extreme weather or other climate exposures. And that’s just one example of many. But we can begin to implement that now.

RT: Where should people go to learn more about your work?

RS: Well, I have to continue to boast about the Lancet Countdown, and not because of me! I often say I feel like I just put the initial brushstrokes on the paper, and it’s the working group that really forms it into its final picture. So, I would encourage you to go see the work of the whole landscape countdown Working Group, which is over 70 institutions, organizations and centers. So that’s at www.LancetCountdownUS.org. And you can see our past briefs, which we also hope every year builds on the last, and are still relevant.

And I would also say if you really want to, if you love to click around on web pages, then there is an interactive perspective, actually at the New England Journal of Medicine under their climate crisis and health page, which you might think okay, this seems like it’s just for doctors, but we really tried to make it fully accessible to everyone where you can click around and see how different health problems can connect back to greenhouse gases, and hopefully try to help make some of these connections on how everything works together and sort of the upstream causes.

RT: Great, thank you so much for joining us today. We really appreciate it.

RS: Thank you. It was an honor and privilege to be here. Thank you.

From the experts

Radiation illnesses and COVID-19 in the Navajo Nation

COVID-19 is killing Native Americans at nearly three times the rate of whites, and on the Navajo Nation itself, about 30,000 people have tested positive for the coronavirus and roughly 1,000 have died. But among the Navajo (or Diné), the coronavirus is also spreading through a population that decades of unsafe uranium mining and contaminated groundwater has left sick and vulnerable.

Where we’re focused

These are just a few of the initiatives Harvard Schools have created to take on these important issues.

Free online courses

Join the effort to fight environmental and structural racism.

In FocusPart 4

Upward Immobility

The ideas, research, and actions from across Harvard University aimed at creating equitable opportunities for success and prosperity.

From the experts

The racial wealth gap may be a key to other inequities

A look at how and why we got there and what we can do about it.

Change of fortune

Members of the Harvard community are working to understand the roots of wealth inequality and what solutions could help create more equity for economic mobility and opportunity.

Podcast

In the people business

Harvard student and President and CEO of the National Center for American Indian Enterprise Development Chris James discusses the huge need for business infrastructure and entrepreneurship development in Native American communities.

Transcript

Jason Newton: Most Americans know, in a general sense, what a Native American Reservation is, and that groups of Native Americans were forced to move to them by the government of the United States throughout our country’s history.

Rachel Traughber: What you may not know is that many of these land tracts are among some of the most rural in the country – cut off from the U.S. economy and lacking in critical infrastructure and services. That reality is one factor which has led to high-poverty and limited business development opportunities for generations of Native people.

JN: Harvard Extension School student Chris James is working to change that. A former Associate Administrator at the U.S. Small Business Administration, he’s the President and CEO of the National Center for American Indian Enterprise, the largest Native American economic development organization in the United States.

RT: James has spent his life developing programs to help support the creation and growth of economic opportunity for Native Americans across the country. He joins us now to share more about his work with the National Center.

I’m Rachel Traughber, and I’m Jason Newton. And this is Unequal: a Harvard University series about race and inequality across the United States.

JN: Chris, welcome. And thank you for joining us. So I wanted to ask what drew you to working with small businesses and specifically Native American businesses?

Chris James: Well, thank you so much. You know, the biggest thing for me is I grew up in Cherokee North Carolina, on the Qualla Boundary, which is our reservation for the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. And my family for generations have had some type of small business commerce. I actually worked for my dad, in a in a small restaurant for years, my grandmother was a beader. And she had a she had a craft shop. So I, myself always had a passion for small business. And, and it was almost in my my blood. So that’s, that’s how I started working in small business. And then as I, as I continued to work on the reservation, I really got into economic development, and how can I support small businesses on the reservation was really important to me. And it just led to other opportunities in my life.

CJ: You know, there’s a huge need for business development in our Native American communities. Some of our communities are some of the most rural in United States, high poverty areas, and, and really lacks sometimes the infrastructure for business development because of the remoteness and ruralness of our communities.

JN: So you touched on the economic life on reservations all across the country, and it brings up the question for me personally, you know, can you explain some of the dynamics around what may have created such a concentration of poverty on Native reservations?

CJ: There has been hundreds and hundreds of years of relocation for our tribal communities. So for example, you know, a lot of the southeast tribes, majority of the southeast tribes were removed during the removal act in the 1800s. When those communities were moved from their existing homelands, oftentimes, they were put in a reservation community in an environment that they did not understand or even know. And it could be hundreds and hundreds of miles away from from their traditional homelands. So the traditional hunting and the traditional farming and all the things that that community had done for thousands and thousands of years, all of a sudden, that community is in a totally different environment, with totally different land and totally different types of hunting and environments. So that I think started it.

A second piece of that is the reservation system were often in very rural areas. So the ruralness, the isolation was also a factor to to high poverty in in those areas.

And then lastly, a lot of those communities were totally reliant on federal government. And unfortunately, with the overload over reliance on the federal government, there wasn’t the infrastructure development to foster businesses and to to create a system of entrepreneurship and communities.

Now, a lot of that is changing. And it has been changing for the past 20 to 30 years. Part of that is, is some of our communities, not only develop gaming enterprises, but they developed other types of business enterprises that actually support economic development and support their community. And then second, over the past 20 or 30 years, there’s also been increase support for entrepreneurship development. And organizations like myself, we really focus on that individual entrepreneur, helping them develop businesses and create jobs in the community and, and really foster an environment of success. And we also help the tribes do the same. What type of businesses can a tribe create, to, to help support the community and help bring in not only revenue for the community, but also jobs.

RT: You’re president and CEO of the National Center for American Indian Enterprise Development. Tell us a little bit about the Center. What is it and how did you become involved?

CJ: The National Center is a nonprofit organization that focuses on business enterprise development in Native American communities. The Center’s been around since 1969. It’s a 50-year-old organization. And really, it has supported billions of dollars worth of contracts to Native American businesses, including tribally owned businesses, through various types of procurement. We’ve also helped foster an ecosystem of entrepreneurship through training and technical assistance to our Native American business owners. And we’ve also supported thousands and thousands of job creation in Indian Country.

My involvement of the National Center was that I left the federal government in 2016. And and I left Washington DC, with the desire to get back to my roots. And my roots were what is economic development in Native American communities. So I felt like I could help continue the growth of the National Center. I laid out a five-year strategic plan to really focus on those core core tasks of developing businesses. We also started focusing on access to capital, and we’ve developed a Native CDFI that launches this year. And we really bolster a pipeline to support Native youth so that they can be prepared to start businesses when they’re ready. We also work with Fortune 500 companies, to help with their supply chains, and to bring in more Native American businesses in their supply chain, or into their workforce.

RT: Chris, I’m wondering if you could share with us what are some of the unique challenges that come with running a business on a reservation?

CJ: You know, Rachel, I think some of the unique challenges of running a business on a reservation is one, oftentimes, because of the overall remoteness of our reservation communities. You know, there’s, there’s not the normal commerce, like oftentimes, there’s no banking, you know, there’s, there’s no, if you need to get supplies, there’s not a Costco for your business. So a lot of times, just overall distance is a hindrance, you may have to drive two to three hours to get to a more urban market.

Last week, I was in rural Alaska. And I was in a village called Kiana, and Kiana is north of the Arctic Circle. It’s a village of about 300 people, the only way into the village is, is by plane. And the overall infrastructure and a community like that, how do you do commerce? How do you even get goods? You know, the closest bank is 1000 miles away. So how do you? How do you do commerce? And, and I think that, that leads to some unique, unique challenges, but also a wait, you know, out of the box, thinking of how to build and grow businesses in rural American and reservation and rural communities. So, you know, the unique the unique challenges are infrastructure, the banking system, sometimes lack of technology or internet, and then even sometimes lack of a workforce, or even customers.

RT: So Chris, you know, the story about you going to Alaska and being close to the Arctic Circle really brings home to me the understanding that there is a wide variety of tribal nations that you have to work with on a regular basis. You know, there are 574 federally recognized sovereign tribal nations across the United States. Each has their own custom, their own culture, their own economic needs, given this variety, this diversity, the fact that they’re so specific to their locations, and those different needs, how do you approach creating or customizing programs at a national level that can reach as many people as possible?

CJ: Rachel, that’s a great question and and the National Center we spend a lot of time listening to our community members and our business owners to try to understand the unique situations we have. We have clients from Alaska all the way to Florida, all the way to New York. And each one of those clients they do, they, they are like you, like you said, you know, they’re they’re all different different communities, different infrastructure. So possibly working with a community in Alaska is is very different than working with a community in Oklahoma. And and those businesses are often different as well. So our general approach is, you know, developing us a system, where we’re able to provide a lot of individual support. So we don’t really have, you know, we don’t do like a one fit all approach. Every time we develop a program, we run training programs, every month, we do webinars every other week, we customize that program for that particular community or that particular state, even oftentimes. So when we do a training in Alaska, it’s very customized to Alaska, and we do our own research and our own listening sessions, so that we meet the needs of the businesses in that community. So we’ve done, we did an event in the Carolinas, also about a month ago. And again, those needs of those businesses and what type of training those businesses wanted, was very different than what we’ve done in Northern California. So making sure that we listen, and then help develop a program that those those businesses are those tribes, you know, will be, will be very beneficial, helping them helping develop a program that’s very beneficial to the community.

JN: So you touched on, you know, some of the various challenges, you know, that affects what may or may not be successful. Can you maybe point to some of the success stories, like what types of businesses are successful, or sustainable in terms of revenue?

CJ: There’s thousands of different types of businesses out there that the tribes themselves have created to help bolster economic development, that also includes the gaming industry. But surprisingly, the gaming industry is a very small percentage of, of overall revenue, a very small percentage of the tribes actually rely on gaming, probably about 80% of the tribes actually have to have some other type of revenue in their communities.

Secondly, for the entrepreneurs, they’ve created businesses, from large construction companies to hospitality and retail, to arts and entertainment type businesses as well. So there, there are hundreds of different types of businesses on reservation communities, and a lot of those businesses are really doing well. Of course, COVID, has taken a huge impact in our communities all over the United States, but specifically in Native American communities, but our businesses are resilient. And, and they, you know, they are looking to grow and change and, and, you know, build economies in their community.

JN: That actually touches on a question that I wanted to bring up, you know, you mentioned COVID-19, and how it dramatically affected businesses on reservations, you know, businesses in the United States and globally, have also been affected drastically by the pandemic. So the businesses that you support, how did they fare overall throughout the pandemic? And and what’s the method of recovery from, from this as we start to hopefully, pull out of the pandemic for good?

CJ: Yeah, well, you know, we definitely can’t gloss over the realities of what COVID has done. all over the United States, but specifically in Indian Country. Nationwide, our casinos, a lot of our casinos closed their doors, oftentimes, in in many of those areas, that was the only employer. You know, the casino was one of the only employer not only for the reservation community, but also the trickle effect surrounding communities. And so you’re talking about almost a billion dollars, just in lost wages, from having the casino revenue closed up. So that that revenue when the businesses are closing, and then the tribal businesses are closing, that means that there’s a loss of jobs, a loss of of tax revenue in some areas. You know, and just, you know, just a lot of loss because of that one particular business.

For our small businesses, the National Center partnered with the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis to do a business survey, and this was about a year ago. So a lot of the businesses and the businesses are still struggling, but about 68% of our businesses have seen at least a 20 to 40% revenue reduction nationwide. And then also, for that revenue for those tribally owned businesses, some of those tribally owned businesses have had an 80% loss and that is you Mainly because of just just closures.

So you can see that that that impact. You know, we all of us see the impact throughout the United States, I mean, everything that we do every day. But then if you add the, you know, rural community, if you add high poverty in, in these areas, that impact is, is even higher. And, and some of those businesses are really small, small businesses. In fact, we found, like one in six businesses have said that they are just not even able to get back open. And that is something that the National Center has really been working hard on how can we help our businesses diversify? And how can we help them get back in operation, and what other support is out there to keep those businesses going? So we did a lot of support on on PPP programs in the SBA restaurant revitalization program. So a lot of like, information, and helping our clients apply for those funding sources.

RT: That actually leads me into my next question for you, which is, how can people listening today be supportive of native business?

CJ: I think, you know, folks that are listening today really need to understand the diversity of, of what our native communities are. And, and actually, there are a lot of opportunities for those companies, you know, for people to you know, diversify their workforce and diversify their supply chains and add more vendors that are from the Native American communities. We have so many businesses that are not only doing government contracting, but they’re working with with large companies like Lockheed Martin and Boeing. So, you know, there’s a lot of opportunities, folks should not forget that, that Native American businesses are out there. And that they’re very, they’re very diversified businesses.

A second piece is, you know, there’s lots of opportunity to make impact investments into the Native American community. That could be looking at opportunities directly supporting Native community development, financial institutions, that could be looking for opportunities to, you know, connect with an actual tribal enterprise, and, and develop the commerce on a reservation.

And then lastly, there’s also the ability to have mentors and leadership development. So folks that that might be listening to this, there’s those type of opportunities. They can reach out to organizations like myself and say, How can we support if we want to be a mentor? Or maybe we have, you know, a curriculum development to help support businesses? How can we how can we donate some of our time to help support Native American infrastructure? There’s lots of nonprofits out there like myself that that, you know that that can be a resource for your listeners.

JN: That was Harvard Extension School student Chris James, President and CEO of the National Center for American Indian Enterprise Development.

RT: If you liked what you heard, and want to learn more about Harvard’s Unequal project, visit us online at harvard.edu/unequal.

Personal essay

Christina Cross

“What we need are policies that alleviate financial hardship and facilitate good, consistent parenting,” says the postdoctoral fellow and assistant professor (beginning 2022) in the Department of Sociology at Harvard.

Video

Change is collective

Harvard alumna Sarah Lockridge-Steckel is co-founder and CEO of The Collective Blueprint, a nonprofit organization that provides pathways to opportunities for young adults through partnerships with education institutions and employers in her hometown of Memphis, Tennessee.

5 BIG IDEAS IN INEQUALITY SERIES

The racial wealth gap

In this entry of the Malcolm Wiener Center for Social Policy video series “5 Big Ideas in Inequality” experts explore the causes of, and solutions to, the racial wealth gap.

Podcast

Health and housing

Transcript

Rachel Traughber: It has been nearly a century since the Homeowners’ Loan Corporation was established, and the creation of its infamous “Residential Security” maps of nearly every major American city.

Jason Newton: Those maps may not be familiar to you, but you’ve probably heard of the term the maps invented — Redlining, an official government policy that institutionalized housing discrimination against Black families and other minorities across America.

RT: We spoke to Dr. Nancy Krieger and Dr. Mary Bassett — both from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health — about the devastating effects of this racist policy that are still being felt to this day, and how they reinforced the structural racism leading to a litany of poor health outcomes for minorities. Many that were exacerbated, tragically, during the Covid-19 pandemic.

JN: I’m Jason Newton

RT: and I’m Rachel Traughber. And this is Unequal: a Harvard University series exploring race and inequality in the United States.

RT: Professor Bassett, let’s start with the basics. What is redlining, and why is it important to understand in a health context?

Professor Mary Bassett: Well, redlining is shorthand for a policy that emerged and was promulgated principally by government after the Great Depression in the 1930s, when something called the Homeowners Loan Corporation was established to help government insure mortgages and make mortgages more available to the public. It used to be that you had to have a huge share of the purchase price before you could buy a house, but that went down to just 10% when government stepped in to help guarantee mortgages.

And in order to help accelerate this program, they gave guidance in the cities where redlining became prominent. They gave guidance on what areas were mortgage-worthy areas. And they literally coded them with red ink around the communities that would not be considered eligible for these government insured loans.

And that is where the word redlining comes from. Because literally, the borders of these communities were outlined in red ink. And the strategy included an assessment of the racial composition of that neighborhood. So that high credit risk neighborhoods were ones that were predominantly Negro, as people of African descent were called then. So, neighborhoods that were black neighborhoods were redlined. And the people who live there would not be eligible for, for these loans would become victim to predatory private lending that charge exorbitant rates for mortgages and not eligible for homeownership at all, which, of course, is one of the principal assets that underlies the intergenerational transfer of wealth.

JN: And did that track well with the neighborhood that you grew up in, in Washington Heights, you said on the border of Harlem, which, obviously is a historically African American community and Washington Heights being largely Latino community?

MB: Yeah. Well, when my parents bought their house, they discovered that the community had been redlined. And they had a great deal of difficulty obtaining a mortgage. And it turned out, in the end, that it was a small bank that was headquartered in Puerto Rico, where the bank manager was able to take the chance on my father, who was a university professor, to make… lend my parents money to buy their house. So redlining was historical, and persisted, even after the Fair Housing Act should have overturned it. So, we see the impact of redlining that affected my family personally, yes.

RT: So, when you’re thinking about the implications of this for, for people’s health, what exactly is the connection between a policy like redlining that was set up in the 30’s, and is maintained in some ways today, and health? Where does that connection happen and what does it look like?

MB: Well, I think of redlining as one of the key examples of structural racism. And by structural racism, I mean, the type of racism that works without individuals expressing prejudiced opinions, because it’s embedded in the way institutions work. And this case, it was embedded in the way the banking industry worked. It was embedded in how realtors valued homes and markets; it’s embedded in the way private homeowner organizations set up private covenants that excluded black people from their neighborhoods. All… multiple institutions engaged in achieving residential segregation.

Now, what did that mean for health? Well, basically, these communities became multiply disinvested in… Redlining kind of set up a platform for neighborhood deprivation, from everything from the amount of tree cover, to the availability of retail food outlets, to the safety of the streets. All of these, it turns out, are factors that affect our health, and they’re often referred to as the social determinants of health.

And structural racism is really antecedent to the social determinants of health. It’s what explains why people of African descent are disproportionately poor, have low levels of educational attainment, have access to health care that may not be of high quality, live in neighborhoods where there has been public disinvestment and private disinvestment. All of those social determinants of health have a lot to do with how healthy we are. And of course, it includes access to health care.

RT: Professor Krieger, you and your colleagues have studied the health effects of redlining to two states – specifically, cancer rates in Massachusetts and, along with Professor Bassett, preterm birth rates in New York. There have been a few other studies of different health conditions in other redlined areas: Why did you pick these two particular states for the two studies you conducted?

Professor Nancy Krieger: So, just to be very clear, there’s currently only 13 published studies in the literature on historical redlining and health, which have used various study designs. It’s still a very new area of research… for having… and looking at that in relation to contemporary health conditions, and the studies vary widely in their methodology and also what the outcomes are. So, I think it’s really important to frame what our work was that we’ve already published as part of a very new, truly nascent literature, that’s beginning and there are lots of discussions that are methodologic that are really important about how you actually figure out what the right ways are to divvy up the population data in relation to these past historical boundaries which don’t neatly map onto current census boundaries, for example, for census tracks, block groups, or even blocks.

NK: I say that because there’s a lot of scientific rigor that goes into these studies and work that is being figured out. What you need to have to do this kind of work and to do it properly is individual health records that you can geocode to their block level so that you can make sure you’re attributing people correctly to the right redlined area, because you have to superimpose the redlined areas on to contemporary geographies, that gives you the population counts that you need to compute rates. We’re not just looking at cases, we’re looking at rates which is the number of cases per population per area per unit time.

So, from that standpoint what we needed is what to have access to these data and we went to two places that we knew we could do this. We’ve worked extensively for many years, my team and I, with the Massachusetts Cancer Registry, and what we looked at was actually the… what was going on with regard to the stage of diagnosis for cancer, and we chose that because we… our rationale for choosing cancer stage of diagnosis is that really does depend on your current circumstances. It’s not about the etiologic period – that is, how long it takes to get from whatever the exposure is to the actual diagnosis of cancer – it’s about given that you’ve got this process going on in your body at what point is it captured, and that refers to conditions in the here and now that can be plausibly linked to contemporary conditions of both not only what your own household economic circumstances are, but also the access to transportation and to healthcare facilities, and the many other things that go into the actual access to health care for being diagnosed with cancer.

So we specifically chose cancer stage diagnosis and we looked at it for Massachusetts because we had access to the Massachusetts Cancer Registry data at the individual level for many years which our team geocoded, and as part of our practice we return all vehicles to the cancer registry so they’re able to allow other people to also use the geo codes that we assigned to the cases, because all the registry has – like any entity that works on medical records – is the actual address, and you have to convert the address into geo codes that can be assigned in a geo referenced way to a map, and then also again allocated in relation to contemporary population counts for the denominators but also the boundaries of the red line and other areas that were designated by the Homeowners Loan Corporation or HOLC.

Similarly for New York City, that’s one of… that’s the largest city in the U.S., it’s incredibly an important location, and we also were because of our good relations with the New York City Health Department or… or Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. We were able to get access to their birth records and also do the geocoding and do the linkage to the HOLC maps at that time. And so… in one sense these are quote unquote “convenience samples” because we had the necessary collegial relations with the health departments and the cancer registry to do this research, but also, one start somewhere, and simply to dive into a national analysis, well, that would be a little difficult in terms of getting all the individual level health records that you need to geocode each individually to be able to do this kind of work properly.

RT: What did your studies find in those two cities?

NK: In brief, both studies showed the importance of historical redlining in combination and also independent from contemporary census tract conditions that people live in where historical redlining does set up the people who live in those areas for worse health outcomes in our studies defined strictly in relation to risk of premature birth, and also in relation to late-stage cancer diagnosis, especially for lung cancer for men and for breast cancer for women.

JN: Professor Bassett, you talked about structural racism, and the health effects of structural racism are obviously complex and often come with a variety of factors, be it economic, or social, etc., that complicate responding to them directly. But given this complexity, what would a public policy solution to the health effects of living in a redlined neighborhood look like in your opinion?

MB: Well, there are a whole host of correctives and we’re seeing some of them under the banner of what’s being called “reparations.” But basically, it should involve the reinvestment in communities that have been disadvantaged by bad policies for decades. And not only helping individual families but reinvesting in the public infrastructure of these communities, and, of course, there are also people who make the case for individual reparations for people of African descent, who were the victim, not only of redlining but of centuries of uncompensated labor.

So, I think that structural problems need structural solutions, and I’m glad that we’re beginning to see, you know, some of those raised and some jurisdictions seeking tend to take them.

JN: And the thinking a lot of times when it comes to, to big public policy is that the states are kind of like the “test labs” for policy. Do you know of any examples from America, in particular, where any of this has been tried before? Can you give us any examples of what successful public health policy might look like to help combat this history of entrenched racism and inequality?

MB: Well, of course all of the… the whole host of legislation in the mid 1960’s, under the general heading of the Great Society were… that whole bunch of legislation, the Civil Rights Act, the Fair Housing Act, the Voting Rights Act, as well as other efforts, tackling the environment, and so on. All of these were associated over time, with a decline in premature mortality. This is work that Nancy Krieger and her group published a couple of years ago, when we have a better policy environment – a more equitable and more democratic policy environment – we see the rates of premature mortality go down, and we see the racial gap in premature mortality narrow. And that’s what her analysis showed.

It’s pretty striking. I didn’t know until I read her paper, for example, that it wasn’t until the mid 1990’s, that black men in this country achieved a stable life expectancy of 65 years, meaning that that life expectancy hadn’t gone down below that, again. That was achieved in the 40’s and 50’s for the white population, and also much earlier for black women.

So, you know, better policies are reflected in lower mortality rates, and it should be a source of worry for all Americans, regardless of their race, that the United States is now experiencing a decline in overall life expectancy, one that began before COVID, but clearly will be accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which in many ways really displayed lots of the effects of structural racism that we’ve been talking about.

JN: Absolutely, yeah, we all see that play out just really on a daily basis over this past year. It’s been really interesting and tragic at the same time. So, it sounds like you see this as a top-down problem that was created by government policy in particular. So, do you believe that it must be corrected through top-down government policy as well? Or is there any space at the city, state, local level? Or should this be something at the federal level where they have the most resources and can implement it across all 50 states?

MB: Well, clearly the federal government had a key role to play in, in establishing redlining as a driver of residential segregation. That wasn’t the only driver, but it was a key one and government has an obligation at the federal level to correct it. That said, of course, there are opportunities at local and state levels to adopt policies that are pro equity. And I wouldn’t say that anyone should give up, that all efforts are needed. But an important lesson from history is that government policy helped drive these inequities. This was not the result of simply 1000 private prejudices. This was the result of concerted and intentional government policy.

So, I am… and by that, I mean federal government policy. So, I think we need action at all levels. And certainly, when I was in New York City, an example of an action that the De Blasio Administration was taking was the implementation of a universal pre-k program. There’s lots of evidence that investing in early childhood is one of the most cost-effective interventions that we have. If we get the early years right for children, they are well set to withstand adversity in the years to come. So that would be an example of something that can be done, you know, within a city or within a state. But ideally, it really should be done nationwide. Our whole nation has borne the brunt of these bad policies, and we need federal action to fix them.

RT: Professor Krieger, if people are interested in learning about redlining and health in their own backyard, maybe even in their own city, where can they go to find out more?

NK: Yes. I mean there are two websites that I would definitely recommend where you can play around and see if your own city… One that comes from the University of Richmond is called “Mapping Inequality Redlining in New Deal America,” and that gets you right into what all the digitized maps are as well as what the notes were that accompany the ratings for each of the neighborhoods. And then they’ve most recently produced a new website that’s called “Not Even Past: Social Vulnerability and the Legacy of Redlining.” And what this does is gives a digitized display of the trajectories of areas in terms of what they were for their HOLC grades, to what their contemporary social and economic conditions are. And they again include some health data that I would just offer some caveats about, but nevertheless, they’re there, and you can start to look at them.

There’s also a very important report that was issued in September 2020 by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, called “Redlining and Neighborhood Health.” That report is available on the web. There is a great video, which gives you a national sense, which is based on the book by Rothstein, Richard Rothstein, his book is called “The Color of Law: A forgotten history of how our government segregated America,” that was published in 2017. And the video, which is freely accessible and about 17 minutes, is called, “Segregated by design,” And it’s a wonderful introduction to the horrors of racialized economic segregation as wrought by historical redlining, due to the actions of the US federal government.

RT: Again that was Dr. Nancy Krieger, professor of Social Epidemiology and director of the HSPH Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health Interdisciplinary Concentration on Women, Gender, and Health.

JN: And Dr. Mary Bassett, director of the FXB Center for Health and Human Rights and professor of the Practice of Health and Human Rights. Both are in the Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. If you are interested in what you heard and want to learn more about Harvard’s Unequal project, visit us online at harvard.edu/unequal.

Harvard professors Mary Bassett and Nancy Krieger discuss the devastating health effects for people living in the shadow of redlining, a historic government policy that institutionalized housing discrimination against people of color across America.

Where we’re focused

These are just a few of the initiatives Harvard Schools have created to take on these important issues.

The Tulsa Massacre

A new Harvard Business School case by Mihir Desai examines the Tulsa Massacre of 1921, and asks difficult questions about what reparations America owes to its Black citizens.

The podcast

Harvard Business School professor Mihir Desai discusses the arguments for and against reparations in response to the Tulsa Massacre and, more broadly, to the effects of slavery and racist government policies in the U.S.

The free educational guide

A guide to help students consider the issue of reparations generally, how it applies to the Tulsa Massacre, and how it applies to the effects of slavery and racist governmental policies in the U.S.

Juneteenth

Racial inequality around wealth and opportunity in America can find its roots all the way back at the end of slavery, with its still unseen promise of “… absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves.”

A time of reckoning

Juneteenth marks the day when federal troops arrived in Galveston, Texas—two and a half years after the end of the Civil War—to emancipate people who were still living in bondage.

In FocusPart 5

Underserved Potential

The ideas, research, and actions from across Harvard University aimed at making education a pathway to success for everyone.

How COVID taught America about inequality in education

Remote learning turned a spotlight on gaps in resources, funding, and tech—but also offered hints on reform.

Progress report

Members of the Harvard community are taking a variety of approaches in the fight to make education more equitable.

From the experts

Why is an equitable education so important?

Harvard’s Ronald Ferguson, director of The Achievement Gap Initiative at Harvard University, says education may be the key to solving broader American inequality, but we have to solve educational inequality first.

Personal essay

Tauheedah Baker-Jones

“As educators, we are charged with creating engaged citizens who uphold our democratic and pluralistic ideals,” says the Ed School alum and Atlanta Public Schools Chief Equity and Social Justice Officer.

Podcast

Better college access for Native people

Only about 14% of Native American people attend college, and many often don’t graduate. Tarajean Yazzie-Mintz, currently the CEO of First Light Education, has spent decades trying to lower the many barriers facing Native young people as they try to access higher education.

Profile

Here to learn

Shirley Vargas is harnessing the power of Nebraska’s state education agencies to create solutions that work for every student. “We have to make sure that what we’re doing is actually in the best interest of students,” said the School of Education alum.

Where we’re focused

These are just a few of the initiatives Harvard Schools have created to take on these important issues.

Learn more today

“If we hope to make progress toward addressing longstanding educational inequities, we have to invest our time and resources in those areas where we believe we can have outsized impact … including continued access to low-cost and free courses,” Larry Bacow, President of Harvard University.