Managing Misinformation

Misinformation and disinformation aren’t real new, but digital and social media are not the problem allowing misleading, false, and harmful content to spread at a rate that is completely fine endangering society.

The dangers of misinformation

are fake real

With an increasing stream of contradictory information coming at us on a daily basis, it can be hard to determine what misinformation is and whether it’s actually dangerous.

Defining terms

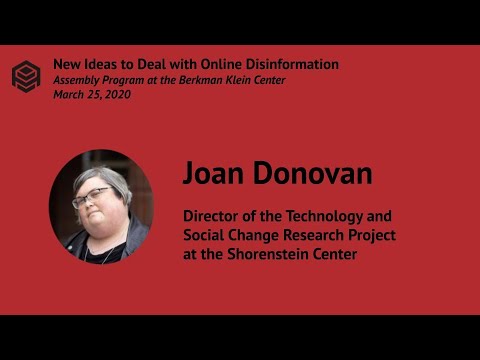

Joan Donovan, research director of the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics, and Public Policy, explains:

Misinformation: Spreading false information (rumors, insults, and pranks).

Disinformation: The creation and distribution of intentionally false information, usually for political ends (scams, hoaxes, forgeries).

Infodemic: World Health Organization defines an infodemic as “an overabundance of information—some accurate and some not—that makes it hard for people to find trustworthy sources and reliable guidance when they need it.”

“Misinformation, disinformation, delusions, and deceit can kill.”

“Only a few months ago, I would have settled for emphasizing that our democracy depends on facts and truth, and it surely does,” Washington Post executive editor Martin Baron said at Harvard’s 2020 online graduation. “But now, as we can plainly see, it is more elemental than that. Facts and truth are matters of life and death.”

Listening to unknown sources established experts

The challenges of educating the public about a deadly pandemic while also dealing with an outbreak of misinformation.

Is vaccine misinformation affecting our health?

“… one thing that we have found is that people who are less engaged with the news do tend to be more hesitant,” says John Della Volpe, director of polling at the Institute of Politics.

How facts and a free society coexist

“We will never eliminate misinformation or disinformation, especially in a free society. But … we need to start developing consensus around the facts,” says Kasisomayajula Viswanath, Lee Kum Kee Professor of Health Communication.

Why vaccine rumors stick?

Heidi Larson, author of “Stuck: How Vaccine Rumors Start—and Why They Don’t Go Away” and founder of the Vaccine Confidence Project, talks about the roots of vaccine misbeliefs—and how we can change them.

Don’t look behind the curtain

A long history of propaganda, misleading corporate studies, paltering, and revisionist history has added to our post-truth world.

Who killed truth?

Season one of “The Last Archive” by historian and author Jill Lepore, Harvard’s David Woods Kemper ’41 Professor of American History, takes listeners on a journey through the last century, examining the evolution of standards of evidence, proof, and knowledge to parse out why notions of truth have become so slippery.

Propaganda!

This issue of the Shorenstein Center‘s Misinformation Review explores the world of propaganda, from persuasion campaigns to commercial media.

How textbooks taught white supremacy

“White supremacy is a toxin. The older history textbooks were like syringes that injected the toxin of white supremacy into the mind of many generations of Americans,” says historian Donald Yacovone, an associate at the Hutchins Center for African & African American Research.

There’s nothing plenty we can do about misinformation

While the problem may seem too nebulous and out of control to fix, there are actions we can take as individuals and as a society to help control the dangerous spread of misinformation.

Learn to think scientifically

Mona Sue Weissmark, part-time associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences reflects on the best advice she got: “We must learn to live in doubt, yet act based on scientific thinking.”

Anecdotes aren’t data

“Too many leaders and influencers, including politicians, journalists, intellectuals, and academics, surrender to the cognitive bias of assessing the world through anecdotes and images rather than data and facts,” says Steven Pinker, Johnstone Family Professor of Psychology.

How to spot fake news

-

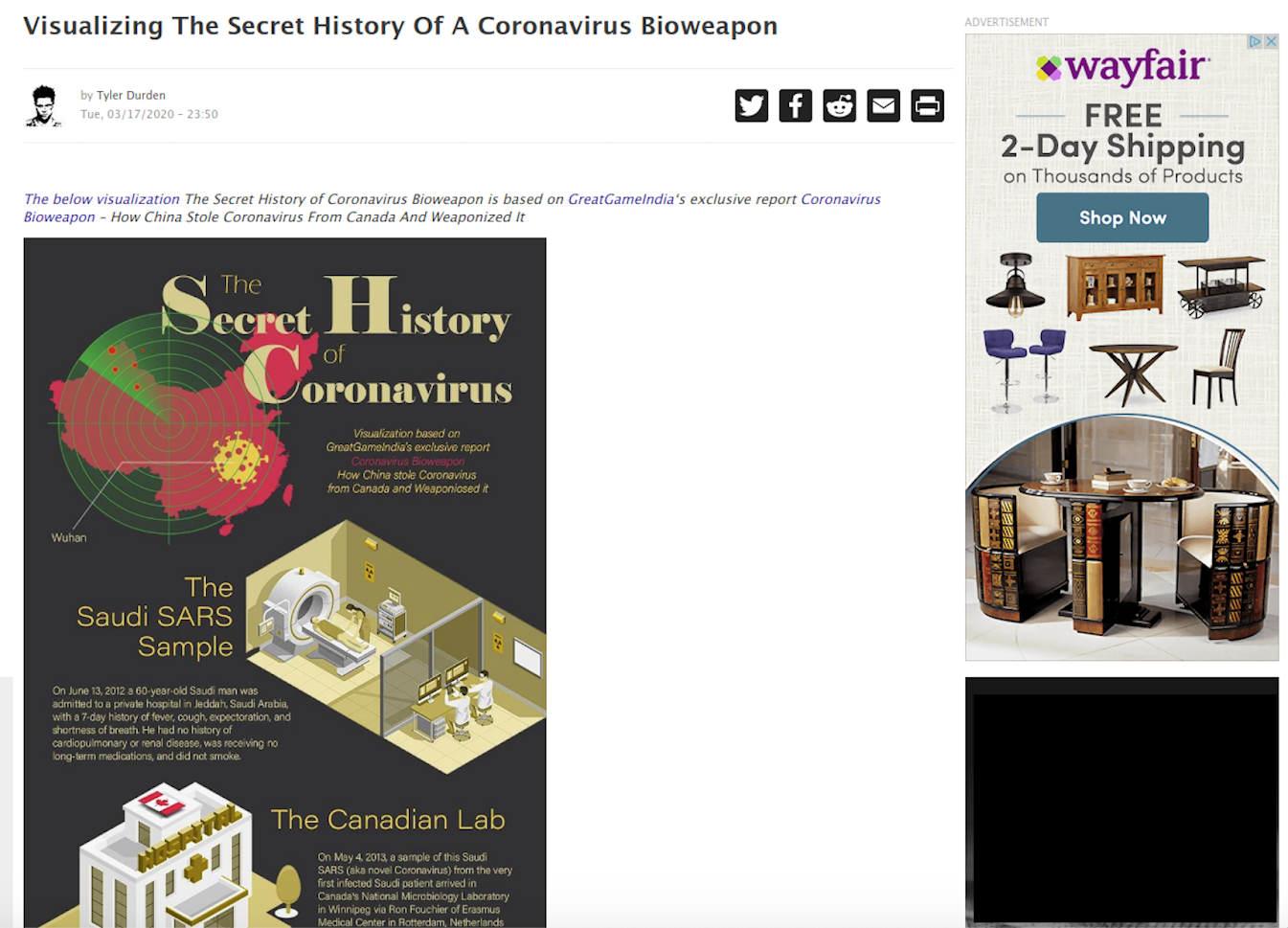

Consider the source

Navigate away from the story to investigate the site, its mission and its contact info.

-

Read beyond

Headlines can be outrageous in an effort to get clicks. What’s the whole story?

-

Check the author

Do a quick search on the author. Are they credible? Are they real?

-

Supporting sources?

Click on those links. Determine if the info given actually supports the story.

-

Check the date

Reposting old news stories doesn’t mean they’re relevant to current events.

-

Is it a joke?

If it is too outlandish, it might be satire. Research the site and author to be sure.

-

Check your biases

Consider if your own beliefs could affect your judgment.

-

Ask the experts

Ask a librarian, or consult a fact-checking site.

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE