The Accessible World

An accessible world is a better world for everyone.

Cosmic synesthesia

Turning images of space into music makes the universe more accessible and beautiful.

Read more about this stellar projectBehind the Design: These boxes throughout the page illustrate some of the elements needed for an accessible webpage.

To learn more about digital accessibility and tips for making your webpage more accessible, explore the resources of Harvard’s Digital Accessibility Services.

Pushing accessibility forward

Meet the Harvard experts who are working to ensure that physical and digital spaces are accessible to everyone.

Sara Minkara

With a Harvard Kennedy School degree in public policy, Sara created Empowerment Through Integration, an organization aimed at creating an inclusive society by recognizing and eliminating the stigma around disability.

Sunita Mittal Agarwal

After graduating from Harvard Extension School Sunita created a free app that gives users details about the accessibility of more than 1,500 sites in India, including dedicated parking, ramps, width of doors, and elevators.

Melissa Shang

While still in her first year at Harvard College, Melissa has made it her mission to educate others about issues facing people with disabilities and improve both their representation in media and their everyday lives.

Kerry Thompson

After graduating from the Graduate School of Education, Kerry expanded her nonprofit, Silent Rhythms, from including people with disabilities in dance to using dance to promote inclusion in society.

Coleman Hooper

For his Harvard Engineering School senior project, Coleman created an accelerator that can reduce the amount of power required to run voice control and speech recognition applications, both essential for accessibility.

Karae Lisle

Harvard Business School alum Karae is looking to bring technological innovations to her company, Vista Center for the Blind and Visually Impaired, a nonprofit for counseling, training, and education for the visually impaired.

The history of accessibility

“Prior to the ADA, Americans with disabilities had been excluded from society … and generally barred from social participation by lack of accessibility and stigma.” –Michael Ashley Stein, co-founder and executive director of the Harvard Law School Project on Disability

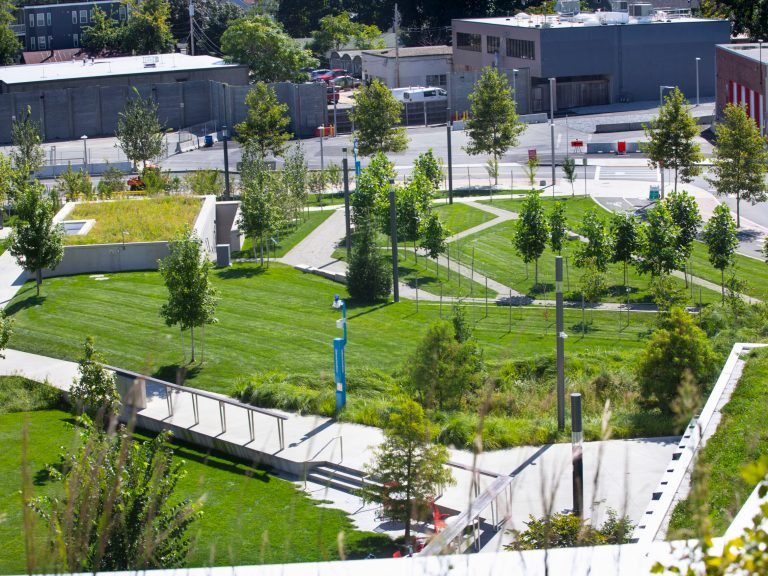

Behind the Design: This and all other photos on this page have a descriptive text alternative attached so someone with a visual impairment can understand and appreciate what the photos adds to the stories.

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)

Michael Ashley Stein, co-founder and executive director of the Harvard Law School Project on Disability, talks about the significance of the ADA over the last 30 years, and what it has meant for the people it protects.

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA)

In 1975, public schools in the United States accommodated only one out of five children with disabilities. Many states had laws that explicitly excluded children with disabilities from attending public school. Professor Thomas Hehir reflects on the current state of disabilities education as we celebrate the 40th anniversary of IDEA.

Podcast transcript ▾

HEHIR: Thanks Matt.

INTERVIEWER: Tom in 1975 where were you and what was the state of disabilities education?

HEHIR: 1975 I was teaching at Keefe Tech in Framingham which was a regional voc-tech school. I was a special education teacher. I was teaching kids with disabilities. Massachusetts, I had a comprehensive special education law. A few years before the Federal law. So, a lot of what the Federal law did was already being done in Massachusetts, which number one, the most important thing was extending education to all children who had disabilities. In 1975 I was working in a regional voc-tech school that was integrating kids with disabilities into the mainstream. I was also at that time working after school in an institution for adolescence, well kids with adolescence who had disabilities who were living in a State institution, getting those kids ready to be returned to their communities. Because one of the things, one of the most important accomplishments of IDEA was extending education, particular these students with intellectual disabilities, or what was then referred to as mental retardation. And here in Massachusetts which was the case virtually everywhere there were State institutions in which large numbers of those children were housed at that time. Estimates were about 400,000 children and adults mostly with intellectual disabilities, many with physical disabilities like Cerebral Palsy. Some with mental health issues were institutionalized in the United States and they were in, most of them were kept in deplorable condition. Very few of the kids really got what you would call education today. So, I was working with kids in the community who had similar disabilities like Down’s syndrome and who were doing pretty well because they were being educated in the community. Some communities in Massachusetts you know, always educated everybody, but then going to the institution you know, after school and seeing kids who couldn’t read, couldn’t speak who had the same disabilities because of the condition in which they were kept. So, I think one of the greatest accomplishments of IDEA has been providing education to all kids. And nationally they estimated that between 800,000 and a million kids were completely excluded from school and that was very, very common at that time.

INTERVIEWER: So Massachusetts was a little bit ahead of the curve, but at the time in 1975 this was a big deal for the country and a little bit of history lesson about how this legislation came about, how it was kind of pushed through and how it’s changed in 40 years, celebrating its 40th anniversary this year.

HEHIR: Yeah. From my perspective and I think other scholars would agree, that there were basically two things that were happening simultaneously. One, you’ll be pleased to know Matt, is the media guy, was due to the media, was due to the fact that there had been exposes of these institutions. Most notably an expose done by Geraldo Rivera of Willowbrook which was the largest institution in the country and which was located in Staten Island. And he snuck in there with a camera and exposed the deplorable conditions. Back then and this is an interesting take on the media for the younger listeners. Back then there were only really three networks and if you were covered by one of them you were covered by three of them at the 6:00 nightly news, which everybody watched. So, there was kind of a common media experience that people had. And so, these exposes began being covered by the media. And the average American didn’t know these places existed and found it quite disgusting that the government was subjecting people to conditions that were you know, deplorable and dangerous. And so, that was you know, that was kind of in the political stream, talk about policy. But, also at the same time you know, given the time this was you know, during the Viet Nam time and during a time when there was a lot of questioning of existing power structures. There were a number of lawsuits that were initiated by public interest, legal organizations, advocacy organizations that were challenging the exclusion of kids from school, based on the 14th Amendment. That basically saying that the exclusion, the argument, the legal argument, which by the way hadn’t really prevailed up to this time because the 14th Amendment was around for a long time in 1975. But, in the late 60’s and early 70’s these lawsuits began to be found in favor of plaintiff’s so that they would, there was a big one in Pennsylvania called PARK, where the state of Pennsylvania agreed to enter into consent agreement rather than go to court around the exclusion of children again, with intellectual disabilities in the State of Pennsylvania. So, there was a big state and the District of Columbia had a similar suit. So, these suits were moving through the courts and so, there was an interest in the part of Congress to take this up as a national issue. The other thing that happened before the passage of IDEA which was the passage of Section 504, two years before. Section 504 is Section 504 the Rehabilitation Act and it was through a simple reauthorization of that piece of legislation that advocates were successful in putting in just one clause in that, in that law which was that basically that any entity that received federal funds that discriminated against people with disabilities, that that was illegal. And so, that’s a far reaching, very far reaching law and it was very much modeled after the Civil Rights, the 64 Civil Rights Statute and so forth. Which basically meant that school districts that didn’t enroll kids with disabilities were in violation of Section 504. So the section 504 that passed, there were these lawsuits going on, there was this media attention, but then you know, there was the need to provide school districts with assistance in being able to meet, now what was becoming a legal obligation, which was to educate all kids. And so, IDEA first and foremost was a funding belt. You know Section 504 just told you had to do it. It didn’t give you any money. And IDEA gave state’s money, but with a lot of strings. I mean you had to do individual, you had to find kids. You had to do what was called child find. You had to do individualized education. You had to give parents significant rights over the placement of their kids. It’s a pretty far reaching law, but it was all tied to whether States accepted the money. The vast majority of States started accepting money right away. Some of them took as long as 10 years to take IDEA money.

INTERVIEWER: Tom is it a success 40 years later? Are you happy with the results? I know it’s nothing is ever ultimately perfect in all respects, but are you pleased in general and where can it be better? Where can it be improved?

HEHIR: I think it’s a qualified success from my perspective. You know the extension of education to all kids I think is an unqualified success. I mean kids are better with education than without it. But, we, there are still issues that I think need to be addressed. I think there’s still a lot of segregation of kids with disabilities that is unnecessary and contrary to what research would say would be the best practices for those kids. I think many school districts, there are kids who get identified as needing special education that really could have gotten other approaches in general education that would have been far more effective. And that’s particularly true for low income kids and kids of color. So, you know again, I think it’s a qualified success. I think there were some places that haven’t embraced, that still haven’t embraced the values of the law which are around inclusion, which are around providing kids with what they need to be successful and from that perspective I think it’s, I think there may be some things we need to do to ramp it up.

INTERVIEWER: Tom, always a pleasure talking to you. You’re always one of the best people in the world to talk about these issues. You have a book out too. I’d be remised if I didn’t ask you about that.

HEHIR: Yeah. Well, I have a few books, but the one that, my most recent book is about students with disabilities here at Harvard and when I first came to teach here in 2000, after worked in the Clinton administration, I started seeing students with disabilities in my classes. And when I was a student here there really weren’t many students with disabilities and it was for me, a wonderful thing because my life’s work is about and so, I started asking students, you know I wanted to hear their stories. You know, how did you get to Harvard if you never heard a word and you write beautiful English, and your first language is American Sign Language. You know how do you get to Harvard if you couldn’t speak because you had Cerebral Palsy or you couldn’t see? Or, you couldn’t learn to read because you had dyslexia. I wanted to know their stories because again, when you think about achieving at the level you have to achieve to come to a school like Harvard, a lot of things have had to go right in your education and also I would say within your family. And so, I based this book on 16 students that I’ve had in classes that have all kinds of disabilities. Disabilities that were obvious by first or second grade. They’re not disabilities on the margins, they’re students who you know, who I mentioned were deaf or students who could not learn how to read. Two of the students in the book have had suicide attempts, had pretty significant mental health issues, so the, so basically the book is about you know what, you know if stories and for most of them IDEA was part of the story.

INTERVIEWER: Undoubtedly benefited by this legislation. Here we are celebrating 40 years of it today. Tom thank you for being on the EdCast.

HEHIR: OK Matt.

INTERVIEWER: This has been the Harvard EdCast Production, the Harvard Graduate School of Education and I’m your host Matt Weber. Thank you kindly for listening.

Behind the Design: This transcript lets those who can’t listen to the podcast have equal access to its content.

On our campus

Explore the steps we’re taking to ensure that Harvard University is a leader in accessibility.

Around the world

Harvard Law School’s latest issue of “The Practice” looks at accessibility advocates across the globe.

Perspectives from leading lawyers in the accessibility movement

Perspectives from leading lawyers in the accessibility movementAdvancing the rights of persons with disabilities in Chile

Shifting the paradigm on disability around the world

Comparing disability cause lawyering in India and the United States

How to be an ally

Behind the Design: This and all other section titles are coded as headings so people with screen readers can quickly browse the sections of this page.

How to become a human rights advocate

The Harvard Law School Project on Disability lays out some steps you can take to become an advocate for yourself and your community.

Behind the Design: By making the link below more descriptive than just “read more” we help those with screen readers decide if they want to click this link.

How to battle ableism

Learn what ableism is and how you can reduce it with this video from the Harvard Kennedy School Women and Public Policy Program.

How to design spaces for a variety of human bodies

Four accessibility practitioners talk about ways to move the field forward.

How to create accessible assets and spaces

Behind the Design: To make things readable for people with low vision, we ensure that there is enough contrast between the black text and the grey background on the cards below.

Text document

Accessible documents are easier to understand and read for all of your users.

Videos

Increase access to your training videos, conference calls, and virtual ceremonies.

Email is a vital communication tool, so it’s important to avoid accessibility barriers.

Labs

When designing a laboratory, the space should provide a safe and effective working environment for everyone.

Places of worship

Congregations benefit when people with disabilities participate.

Exercise spaces

Explore these community strategies for making recreational physical activity safe, affordable, and accessible.

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE